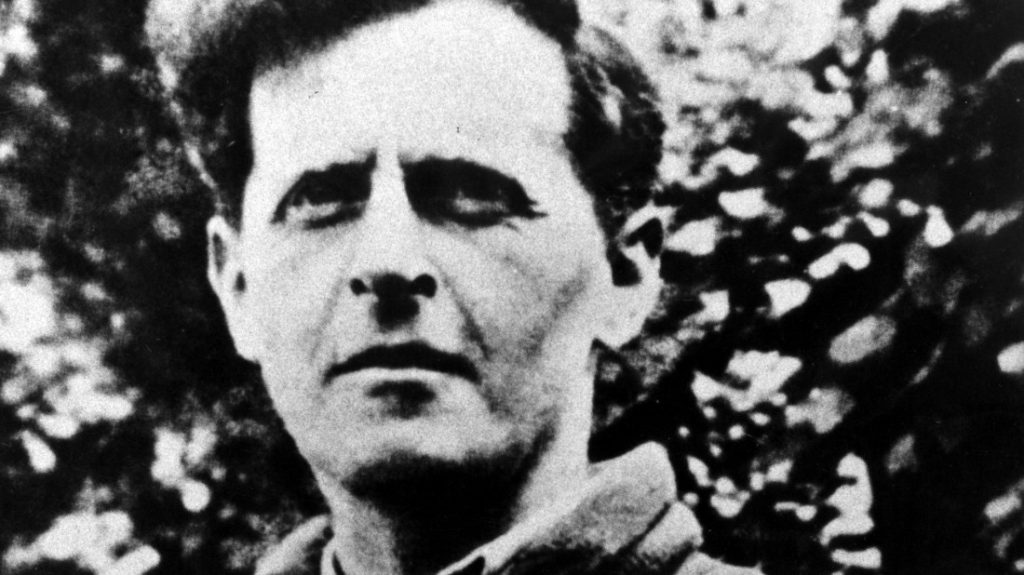

As is known, Ludwig Wittgenstein was not only one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century, but also a passionate teacher. He was subject to corporal punishment to the extent that it exceeded the broad scope of practical education at the time. Then his teaching career ended abruptly. Nevertheless, Wittgenstein remained a teacher, but now he is teaching himself and posterity.

As a musician – he played the clarinet and was well acquainted with Viennese classical and romantic works – he also had something to say about it. However, he never authored the book “Beberatungen zur Musik” which is now published. But he coined the idea that can be found in his manuscripts: “The title of my book: Philosophical Meditations Arranged Alphabetically by Their Subjects” https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/.

Berlin professor of composition Walter Zimmermann has now embraced the idea and has summarized everything on the subject of music that the Wittgenstein Archives in Bergen should present alphabetically in broad terms: from “model types” like fugue, symphony, and waltz to “tones” like keys, pitch rows, scales. Does it make sense? Not necessarily, because Wittgenstein did not provide a model for a lexicon of music, and group sentences for individual keywords rarely explain the facts in more detail. Rather, it is a fixed point around which Wittgenstein’s ideas revolve around and around. Some sounds distant and elusive at first, and others make sense right away.

Ludwig Wittgenstein and Walter Zimmermann (Editors): Notes on Music. Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2022. 253 pages, €25.

For example, when he searches for irony in music and introduces not only Wagner’s “Meistersinger” into play, but also fugato in the first movement of Beethoven’s ninth work: “Here is something that corresponds to the expression of dark irony in discourse.” He ironically equates to “distorted” and comes out with Grillparzer, who said that Mozart only allows beauty in his music. So it is not deformed. Wittgenstein is rightly unsure if this is the case and immediately solves the problem by saying that the term ‘beauty’ has also done some mischief here.

Elsewhere, Wittgenstein is less critical, including himself. Gustav Mahler’s symphonies, for example, which often develop in the alienation of existing music, are felt by Wittgenstein as unoriginal, but rather a lie, a “kind of fraud.” But then it is not an accusation against Mahler so much as an accusation against him: “To lie to oneself, to lie to oneself about his inauthenticity, must have a bad effect on his style; for the result will be that he can no longer distinguish true from false. This It might explain the inauthenticity of Mahler’s style + I’m in the same danger.”

Wittgenstein gets emotional here, finding Mahler’s music to be “bad”, and “not worth anything”, but thinks no more about the criteria used. At this point, “fake” can mean no more than a non-original word, not even a non-original one. Johannes Brahms was accused of this at the time. However, the fact that the essence of a work of art must always be new and unique in order to be recognized as an important art is not a universal norm of the era but shows a narrow perspective, which linked creativity above all to the discovery of catchy melodies. Composers know that it’s not even half the battle.

You have to search for data on the base area of Wittgenstein

Clips like this make you a little sad. How much one could learn about Mahler if Wittgenstein approached him with the same positive precision as, say, Franz Schubert, whose melodies appropriately contrasted with those of Mozart, or if he followed the remark of the mathematician Rudolf Roth that Schumann “through Wagner lost a part much of its legitimate influence.

Even more regrettable, however, is the fact – and here the alphabetical order of the keywords again obscures more than it helps – that one has to find their own data about the fundamental field of Wittgenstein’s language and meaning, i.e. similarity with language and the meaning of music. Here one can expect deeper insights than in the observed descriptions of hands-on musical experience.

Phrases like this point out: “Humans have the ability to construct languages in which any meaning can be expressed without having any idea of how and what each word means.” And in the direction of modern sign theories: “Yes, symbols have the form of color + space and if, for example, a letter designates a color and sometimes a sound, then it is a different symbol in both cases – + this is evidenced by the fact that other syntax rules apply to it “. But where do language and music differ?

Often you can’t think unless you talk to yourself in a low voice

One can call speaking the instrument of thought, says Wittgenstein, but one cannot say that the process of speaking is an instrument of the thought process, or that “language is the carrier of thought, as it were, just as the tones of a song can be called the carrier of words.”

Some long sections in this context have been written in English: one can often think only if one speaks to oneself in a low voice. But no one says that thinking is accompanied by speech unless they are tempted or compelled to do so by the presence of the two verbs: speech and thinking. If anything could be said to accompany or accompany speech, it would be something like modifying the phonemic meanings of an expression. “But does the expression accompany the words in the same sense as the melody?”

The editor refrains from translating, that would be difficult. If one translates the word “accompanied” by the word “accompanied,” one assumes that the sounds are accompanied by a spoken word in the Song language. So it will be pronounced and sung simultaneously in a separate act.

Music does not speak to us at all? We do not mean at all?

Wittgenstein clearly seeks the character of musical meanings in English exaggeration, yet he debunks them as imaginary beings, thereby depriving the reader of the seductive romantic belief: “The melody is a kind of filler, it is complete in itself; it masturbates.” So she doesn’t talk to us at all? He does not mean us at all or part of the art at all? That would be sober, frustrating, and comforting.

Sometimes Wittgenstein’s ideas are a little “blurred”, which means less confusion than almost the opposite, the inevitable consequence of his thinking, the irreversibility of the knowledge he has gained. Mudelt is “like silver paper that, once wrinkled, cannot be completely polished.” There is so much in music to keep a distance from ignorance, and not quite in it to think about it and speak for it. Questions lead. What is missing other than music? What is wrong with a person who does not feel that something is lost when the word ‘bank’ is repeated so often; its meaning; + is now just a sound? Wittgenstein’s answer that a kind of side blindness remains unsatisfactory, the reader has to think for himself. The teacher cannot achieve more.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

Hawaii was canceled by CBS after 3 seasons

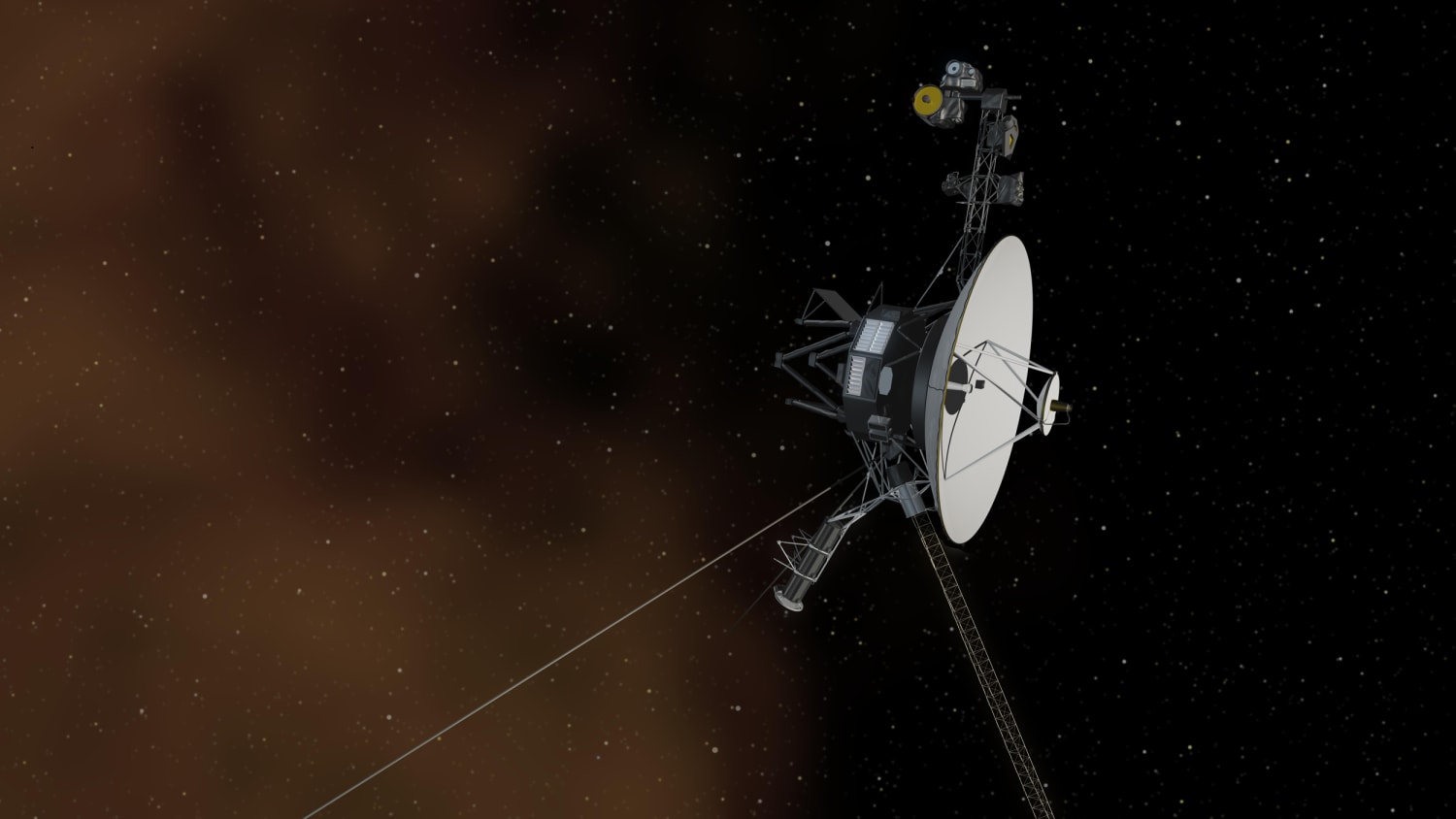

Inside NASA's months-long effort to save the Voyager 1 mission

Poppy Harlow is out at CNN after CNN This Morning was canceled