After working for five months to reconnect with the most distant man-made object in existence, NASA announced this week that the Voyager 1 probe has finally called home.

For the engineers and scientists working on NASA's longest mission in space, it was a moment of great joy and relief.

“That Saturday morning, we all came in, and we were sitting around boxes of cookies and waiting for the data to come back from Voyager,” said Linda Spilker, project scientist for the Voyager 1 mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. California. “We knew exactly what time it was going to happen and it became very quiet and everyone just sat there looking at the screen.”

When the spacecraft finally answered the agency's call, Spilker said the room erupted in celebration.

“There were cheers, people raised their hands,” she said. “And a sense of relief too – well, after all that hard work and going from not being able to get a signal coming from Voyager to being able to connect again, that was a huge relief and a great feeling.”

The problem was with Voyager 1 It was first discovered in November. At the time, NASA said it was still in contact with the spacecraft, and could see that it was receiving signals from Earth. But what was relayed to mission controllers — including scientific data and information about the health of the probe and its various systems — was garbled and unreadable.

That began a months-long campaign to determine what went wrong and try to save the Voyager 1 mission.

Spilker said she and her colleagues remained upbeat and optimistic, but the team faced enormous challenges. For example, engineers were trying to troubleshoot a spacecraft traveling in interstellar space, more than 15 billion miles away — the final long-distance call.

“With Voyager 1, it takes 22-and-a-half hours to receive the signal and 22-and-a-half hours to get the signal back, so we prepare the commands and send them out, and two days later, you can get the answer whether it worked or not,” Spilker said.

The team eventually determined that the problem was due to one of the three computers on board the spacecraft. A hardware failure, perhaps the result of age or exposure to radiation, would likely corrupt a small piece of code in the computer's memory, Spilker said. The flaw meant Voyager 1 was unable to send back coherent updates on its health and science observations.

NASA engineers decided that they would not be able to repair the chip on which the garbled program was stored. The bad code was also so large that Voyager 1's computer could not store it and any newly loaded instructions. Since the technology aboard Voyager 1 dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, the computer's memory pales in comparison to any modern smartphone. That's roughly the amount of memory in an electronic car key, Spilker said.

However, the team found a workaround: they could break the code into smaller pieces and store them in different areas of the computer's memory. Then, they can reprogram the section that needs repair while ensuring that the entire system continues to work cohesively.

This was a remarkable achievement, because the longevity of the Voyager mission meant that there were no effective testbeds or simulators here on Earth To test new pieces of code before sending them to the spacecraft.

“There were three different people looking through the code patch that we would send out line by line, looking for anything they missed,” Spilker said. “So it was just an eye check of the software that we sent out.”

The hard work paid off.

NASA reported the happy development on Monday, Writing in a post on X: “You look a little like yourself, #Voyager1.” Its own spacecraft Social media account responseSaying, “Hey, it's me.”

So far, the team has determined that Voyager 1 is intact and functioning normally. Spilker said the probe's scientific instruments are working and appear to be working, but it will take some time for Voyager 1 to resume transmitting science data.

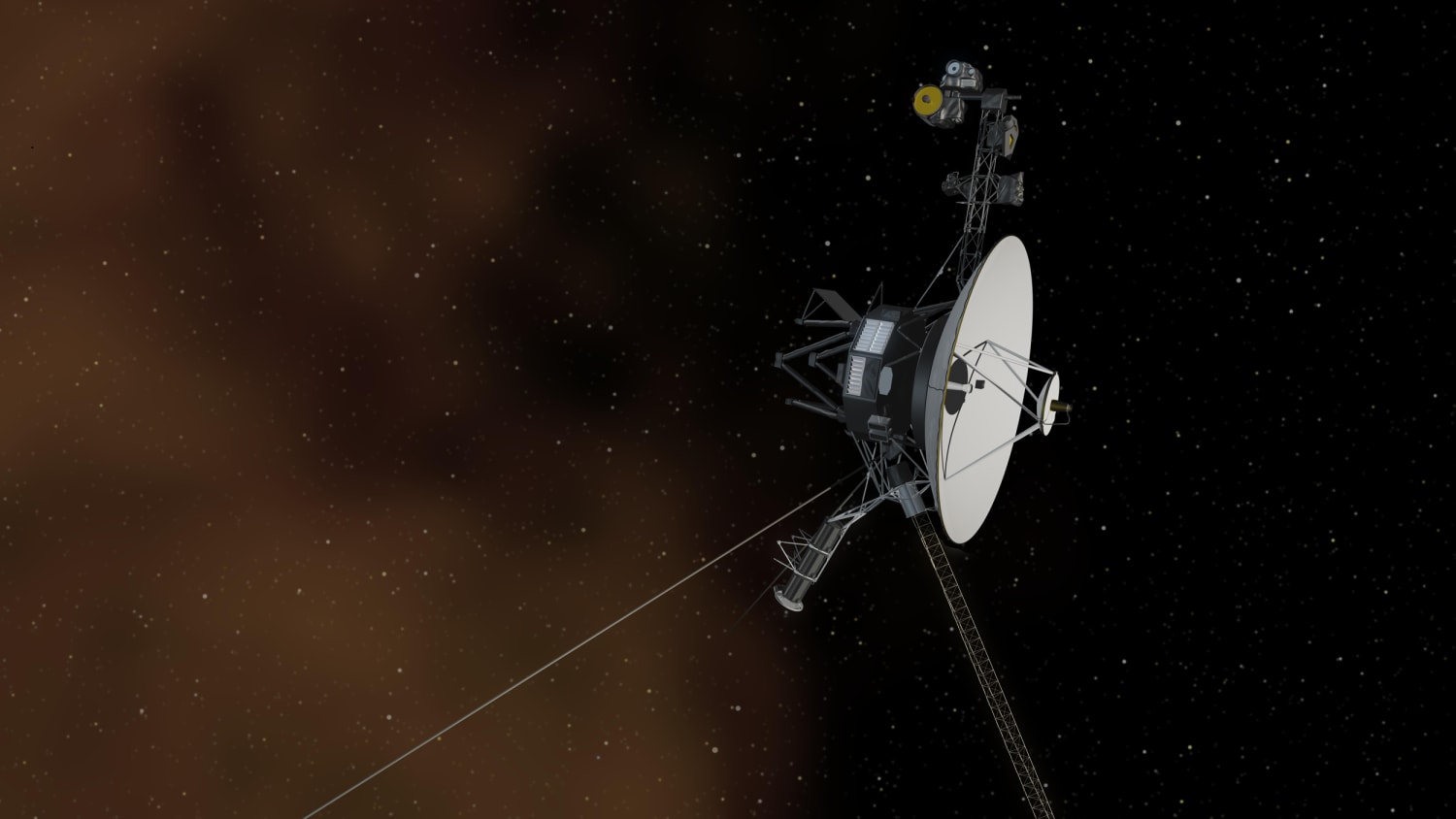

Voyager 1 and its twin, the Voyager 2 probe, were launched in 1977 on missions to study the outer solar system. As it hurtled across the cosmos, Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, studying the planets' moons up close and taking photos along the way.

Voyager 2, 12.6 billion miles away, has had close encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune and continues to operate as usual.

In 2012, Voyager 1 ventured beyond the solar system, becoming the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, or interstellar space. Voyager 2 followed suit in 2018.

Spilker, who first started working on Voyager missions when she graduated from college in 1977, said the missions could last into the 2030s. Eventually, however, the sensors will run out of power or their components will become too old to continue working.

It will be difficult to finally finish both missions one day, but Voyager 1 and 2 will remain “our silent ambassadors,” Spilker said.

Both probes carry time capsules – messages on gold-plated copper discs known collectively as… Golden record. The discs contain images and sounds representing life on Earth and human culture, including excerpts of music, animal sounds, laughter and greetings recorded in different languages. The idea is for the probes to carry messages so astronauts in the distant future can find them.

“Maybe in 40,000 years or so, it will come relatively close to another star and be found at that point,” Spilker said.

“Extreme travel lover. Bacon fanatic. Troublemaker. Introvert. Passionate music fanatic.”

More Stories

Who is the band Gojira that will perform at the Olympics opening ceremony?

SpaceX Moves Crew Dragon Spacecraft to West Coast After Multiple Space Debris Incidents

Stathis Karapanos – Hindemith Review: Complete Works for Flute