Enter native species varieties – or “nativars” (an unscientific term defined as a deliberately selected variety, hybrid, or crossbreed of a native species), the plant industry's attempt to improve nature. For example, if they look at a star that has copious amounts of sparkling blue flowers in the fall, they will imagine that the packaging might look better in pink. It's not just aesthetic changes; Breeders are also focusing on creating plants that are more disease resistant. But are these varieties equally attractive to the insects and birds that depend on them for their livelihood? Researchers have worked to find the answer.

In 2011, Annie White It was just getting started Nectar Landscape Design Studio When she hit a roadblock while trying to find specific native species at local nurseries. To find out whether natural alternatives were equally effective from the point of view of pollinators, I engaged in a doctoral research program. Working with the University of Vermont, White began a field study at two sites in Vermont, collecting data through 2015. She planted 11 native species paired alongside one of the cultivars, then observed nearly 8,000 visits from several groups of pollinators—including Bumblebees, honeybees, small dark bees, beetles/bugs, butterflies/moths, flies and wasps/ants.

Your findings? “Half the time there was a preference for native species, and half the time there was not much difference.” Only 'Lavender Towers', a cultivar of Culver's rootstock (Veronicastrum virginicum), outperformed the species in visiting pollinators. On the other hand, some taxa were noticeably overlooked by pollinators. She bombed the pink-flowered star 'Alma Puschke'. Tradescantia 'Red Grape' also got a thumbs up.

What drove pollinator preferences? White suspected that nectar quantities might play a major role. Flower color and bloom time can also be factors.

Other researchers are also looking for answers. Cuba Mountain Centre In Hockessin, Delaware, it has Trial Garden (Open to the public) Comparative testing of species native to the eastern United States and their cultivars. Primarily, their studies focus on the feasibility of the park. But thanks to the local Pollinator Monitoring Team, a group of 10 to 20 trained volunteers, recent experiments have also collected data on the work of pollinators. They asserted that pollinators favor the indigenous people with whom they evolved. “Genres are always the gold standard,” he says. Sam HoadleyDirector of the Horticultural Research Center.

However, in some cases, pollinators were attracted to the varieties. Experiment with bee balm (Monarda) found that the flowering nativar is bright red Monarda Didyma, Jacob Klein outnumbered the species in hummingbird visits, 273 to 22. Meanwhile, the pale violet nativator Monarda fistula, 'Clear Grace' also outperformed the species in visits by moths and butterflies. Another surprise was Nativar's surprise Phlox paniculata, Hoadley says Gina outperformed the species “by a large margin.”

Bloom time can affect pollinator preferences. Although most fungi overlap species, this is not always the case. Some have a completely different flowering window. Hoadley also says management issues, such as pruning, can make any plant out of sync with pollinators. “Delayed flowering can make them inaccessible, especially for specialist insects,” he says. And specialized insects that depend on a single plant species for their survival tend to pay a price when things get out of sync. “There are a lot of moving parts to consider,” Hoadley says.

Jane Hayes, a graduate research assistant, conducted a similar study at Oregon State University. She planted seven native species alongside their corresponding varieties and observed the interactions of bees, butterflies and syrphid flies over three years. The data is still being analyzed, but Hayes's findings are similar to those of other studies: pollinators generally prefer native species, and those plants also attract more specialized bees and more diverse pollinators.

All of the studies also confirmed what gardeners had long suspected: the closer the nativa is to the original species, the greater the attraction. Dramatically altered flowers, including double echinacea (“Pink Double Delight” in White's study, for example) with petals instead of reproductive parts, only confuse pollinators.

On the other hand, changes in plant size and leaf color do not appear to affect pollinator interest, according to studies conducted at Cuba Mountain. Cultivars with colorful or variegated leaves, or more compact plants, usually perform as well as the parent plant, although larval activity on shrub varieties with red and purple leaves is still being studied.

Overall indigenous people scored relatively well, but there is also a future to consider. If we want to keep plants and their corresponding insect populations healthy and thriving, genetic diversity must inform our choices. Native species have the greatest genetic diversity to create offspring that can survive stress, especially in the face of the challenges of climate change. When gardeners shop locally and look for nurseries that collect seeds of native plants from the surrounding area, the resulting plants will have a set of characteristics adapted to local conditions. Native species, with less genetic diversity, do not have this advantage. For example, in White's studies of Vermont, many indigenous people failed to survive harsh winters.

However, we should not reject national origin completely; They fill a niche. It serves as a kind of introduction to the indigenous world for gardeners, especially those who live in urban areas or in small spaces who want to make an environmental impact with less-than-ideal growing conditions. This is especially true for plants (such as echinacea) that are readily available at local nurseries.

No one should feel forced to be tough, Hoadley says. “Often, indigenous people inspire people to start growing native plants, bringing them into the conversation with confidence that they are doing something good.”

Tova Martin is a gardener and freelance writer in Connecticut. Find her online at tovahmartin.com.

“Extreme travel lover. Bacon fanatic. Troublemaker. Introvert. Passionate music fanatic.”

More Stories

Prince Harry will return to Britain next month

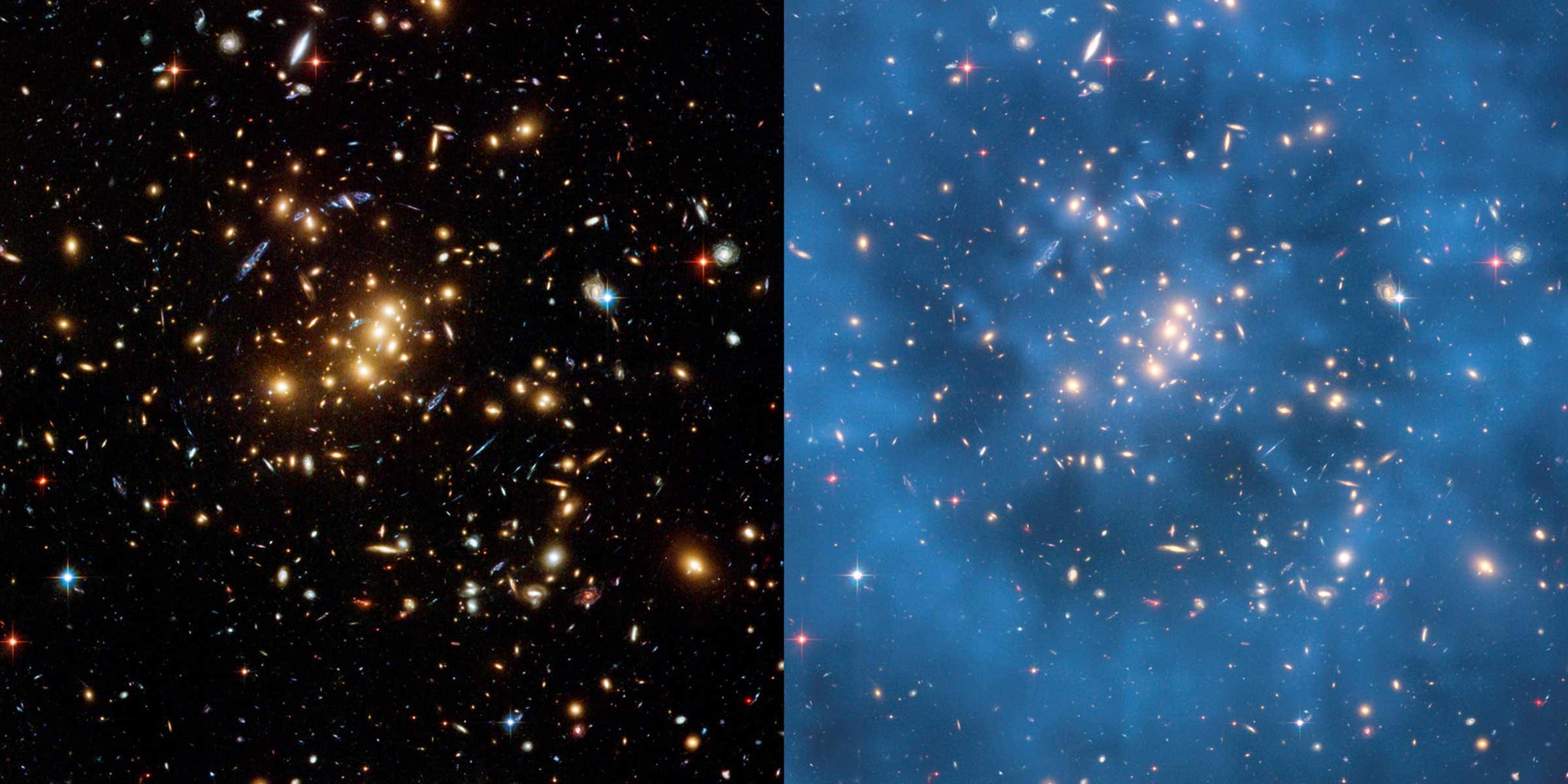

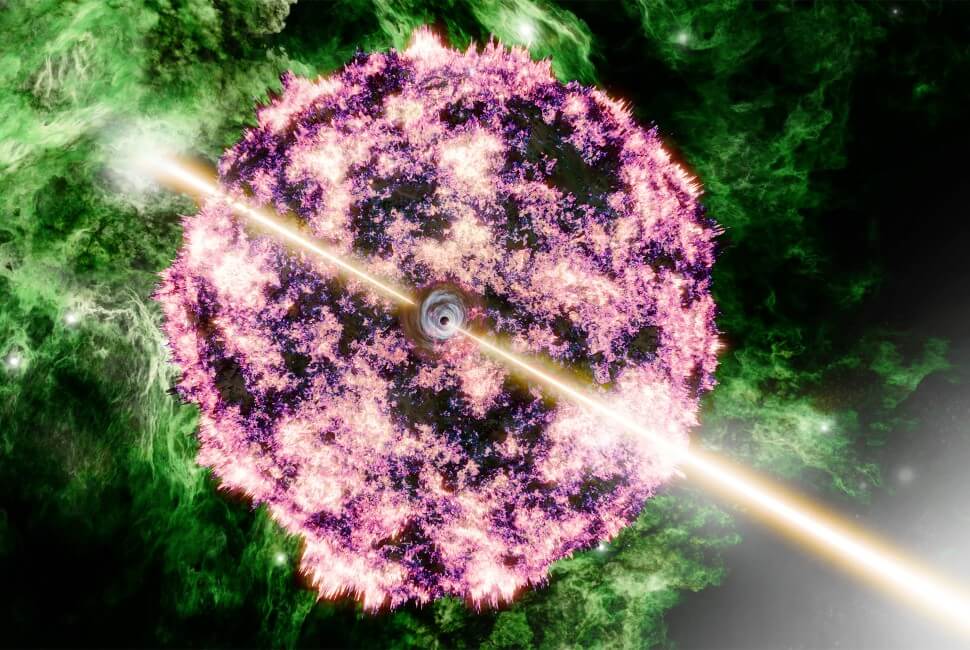

Converting invisible dark matter into visible light

Ellen DeGeneres speaks out about talk show's 'devastating' ending: Reports