A few days before launch, Glenn, right, watches artist Cecilia “Sis Baby” paint the name Friendship 7 on his capsule. credit: NASA

In February 1962, the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union was in full swing. Both countries developed spacecraft to send humans into space and chose a group of pilots to fly those spacecraft. The Soviets leapt forward by putting the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961, in a single orbital flight around Earth aboard the Vostok spacecraft. The United States responded with two experimental Mercury suborbital missions, which were launched atop Redstone missiles. The Soviets then kept an astronaut in space for an entire day. On February 20, 1962, astronaut John H.

Project Mercury was America’s first human spaceflight program. Space mission group in[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, under the direction of Robert R. Gilruth, initiated the project in October 1958 with three goals: orbiting a manned spacecraft, investigating man’s ability to function in space, and safely recovering both spacecraft and crew member. In April 1959, NASA announced the selection of seven astronauts who would undertake the Mercury missions. After some early launch failures, the first successful unpiloted test of the single-seat spacecraft took place in December 1960, launched into a suborbital flight atop a Redstone rocket. A similar flight a month later carried Ham, a chimpanzee. Astronaut Alan B. Shepard completed the first American spaceflight on May 5, 1961, a 15-minute suborbital mission aboard his Freedom 7 capsule. Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom flew a similar mission on July 21 aboard Liberty Bell 7. The first successful unpiloted orbital Mercury flight using the more powerful Atlas rocket flew in September 1961, followed by the two-orbit flight of chimpanzee Enos on November 29. The next step was to fly an astronaut on an orbital mission.

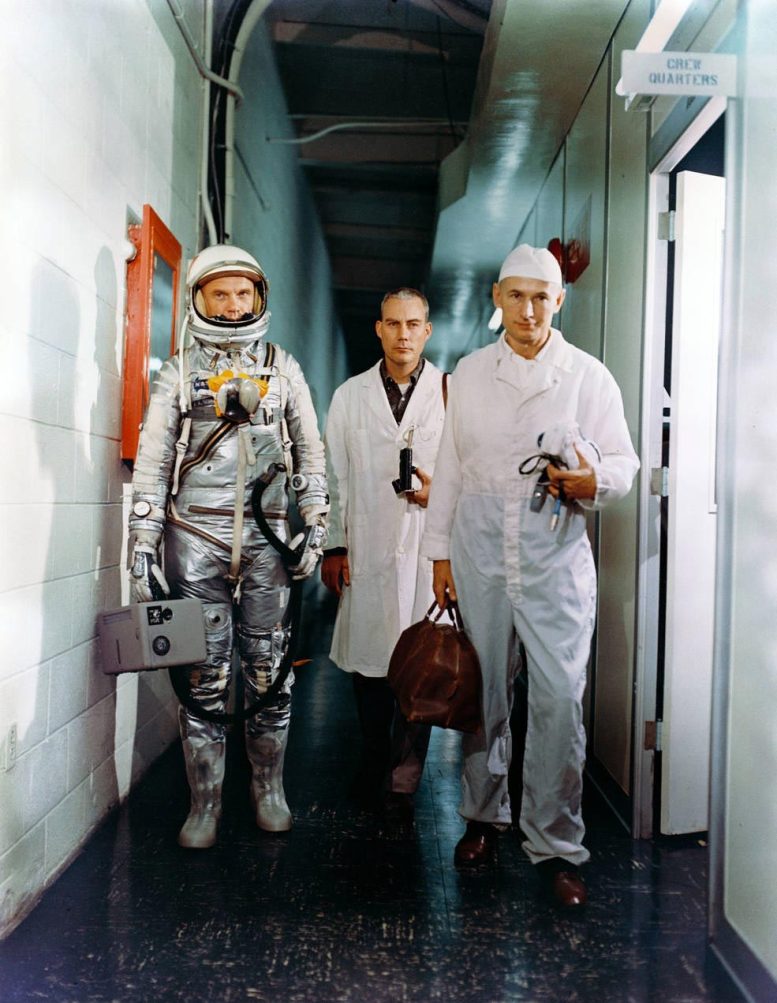

Friendship 7 astronaut John H. Glenn, left, leaving crew quarters with flight surgeon Dr. William K. Douglas and suit technician Joseph W. “Joe” Schmitt. Credit: NASA

On November 29, 1961, Gilruth, by then the director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, announced the selection of astronaut John H. Glenn to fly the first orbital mission, with M. Scott Carpenter as his backup. Following months of training and preparations of the spacecraft and its Atlas launch vehicle, Glenn donned his spacesuit and boarded Friendship 7 for a launch attempt on January 27, 1962. The launch director halted the countdown at T-minus 13 minutes due to thick clouds that would have prevented observation of the rocket’s ascent. Officials rescheduled the launch, and mechanical and weather delays added further postponements. On February 20, after a steak-and-eggs breakfast, Glenn suited up once again in Hangar S, a facility leased by MSC’s Cape Operations from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, today’s Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. He boarded a transfer van that took him on the four-mile, 11-minute trip to Launch Complex 14.

Assisted by the pad crew led by Guenter F. Wendt, Glenn squeezed into the cramped capsule. They strapped him in and bolted the hatch cover in place. After several delays, resulting in Glenn spending nearly four hours in the capsule, the countdown finally reached zero at 9:47 a.m. EST and the Atlas rocket’s three main engines ignited. Four seconds later, the rocket rose from the launch pad on a pillar of fire. Two minutes and nine seconds later, the rocket’s two booster engines cut off as planned and were jettisoned, the Atlas continuing on the power of the single, center-mounted sustainer engine. At five minutes, one second into the flight, the sustainer engine cut-off and Friendship 7 separated two seconds later. Glenn was in orbit!

Liftoff of Friendship 7 with Glenn aboard atop an Atlas rocket from Launch Complex 14 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, in Florida. Credit: NASA

A team of engineers monitored the countdown and the launch from the Mercury Control Center (MCC) located in Building 1385 at Cape Canaveral, led by Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft, who also served as chief of MSC’s Flight Operations. Carpenter served as capsule communicator, or capcom, the one person in MCC who communicated with the astronaut in orbit. A global network of tracking stations located along the spacecraft’s ground track supported the team in the MCC.

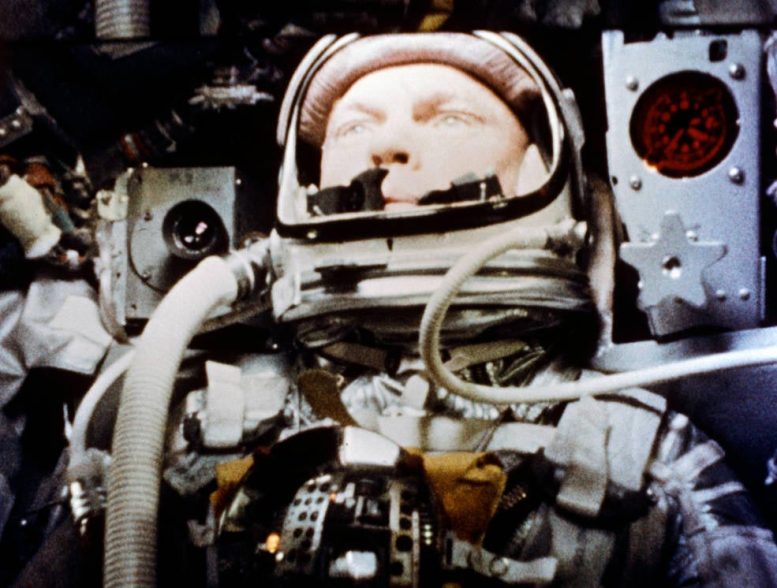

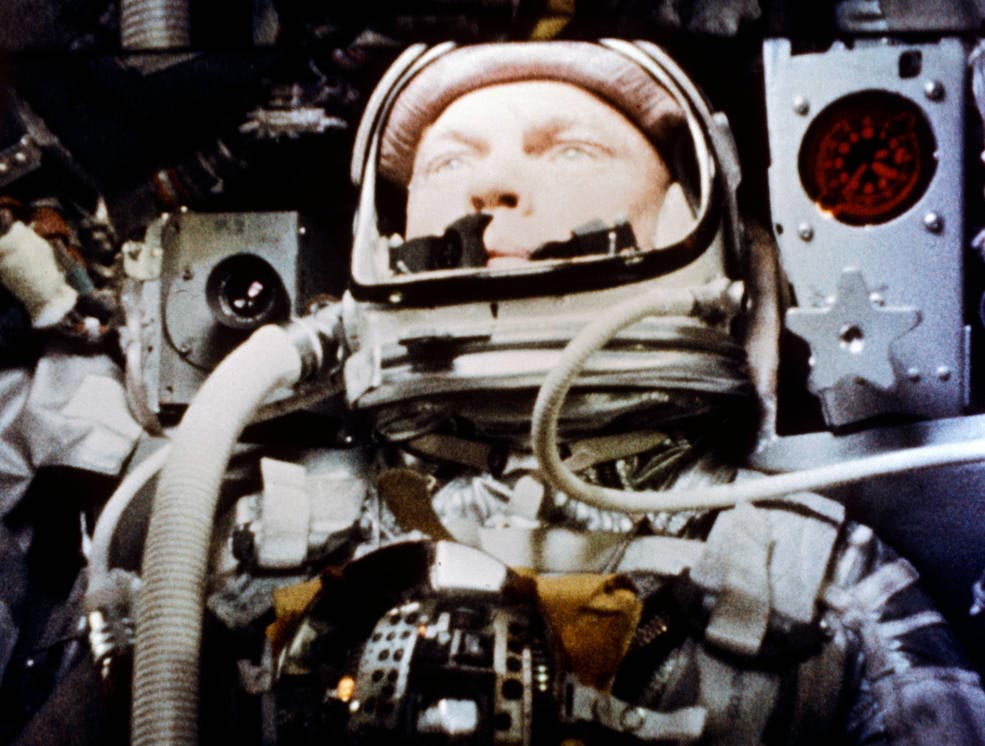

An automatic camera inside Friendship 7 records astronaut John H. Glenn during his orbital flight. Credit: NASA

Shortly after separating from the booster, Friendship 7 turned around, flying with its heatshield in the direction of flight. Looking out his window, Glenn observed the state of Florida, and photographed it with his Ansco Autoset camera. He tracked the booster for eight minutes as it slowly tumbled out of sight. He reported feeling fine in weightlessness, and checking his spacecraft’s systems reported that all were working as expected. During his first orbit, as he flew over the succeeding ground sites, Glenn continued reporting on his and the spacecraft’s condition, successfully controlling the capsule’s attitude. He observed his first orbital sunset over the Indian Ocean and sunrise over the Pacific Ocean, including the phenomenon of the “fireflies,” ice particles traveling with his spaceship illuminated by the rising Sun. He ate his only food during the mission, a tube of apple sauce, and took a xylitol pill as part of an experiment investigating digestion during spaceflight. With all systems operating well, through the tracking station in Guaymas, Mexico, MCC gave Glenn a “go” for his second orbit. When his spacecraft began drifting out of its normal attitude, Glenn easily steered it back to its proper orientation.

As he passed over Cape Canaveral at the start of his second orbit, controllers noticed a signal indicating that the spacecraft’s landing bag, used to cushion the impact at splashdown, had deployed, meaning that the heat shield required for reentry was no longer in place. Although engineers assumed the signal to be erroneous, they came up with the plan to keep the retrorocket pack on after retrofire, hoping the straps would be strong enough to keep the heatshield in place had the landing bag in fact been deployed. Although not told explicitly about the problem, Glenn was advised by all ground stations to make sure the landing-bag deploy switch was in the “off” position. Otherwise, Glenn’s second orbit around the Earth passed uneventfully, with the astronaut conducting experiments and photographing the planet as it sped by beneath him. As he passed over Hawaii, he received the “go” to proceed to his third and final orbit. Controllers instructed Glenn to place the landing-bag switch in the automatic position, and should a light come on, to keep the retropack in place after retrofire. Having now deduced what the issue was, Glenn reported he heard no bumping noises during attitude maneuvers that would indicate a deployed landing bag. Nearing the California coastline, the spacecraft fired its three retrorockets to slow its velocity, with Glenn reporting, “Boy, feels like I’m going halfway back to Hawaii!” Engineers closely monitored Friendship 7’s reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere. The temporary radio blackout caused by the buildup of ionized gases around the spacecraft as it sped through the upper layers of the atmosphere occurred as planned, lasting four minutes, 20 seconds. Glenn described the reentry as “a real fireball outside,” as pieces of the retropack burned off and passed by his window. He manually controlled the spacecraft’s attitude during the entry, eventually exhausting his fuel supply. The drogue parachute deployed early at 28,000 feet to slow and stabilize the spacecraft, followed by the main 63-foot red and white main parachute at 10,800 feet.

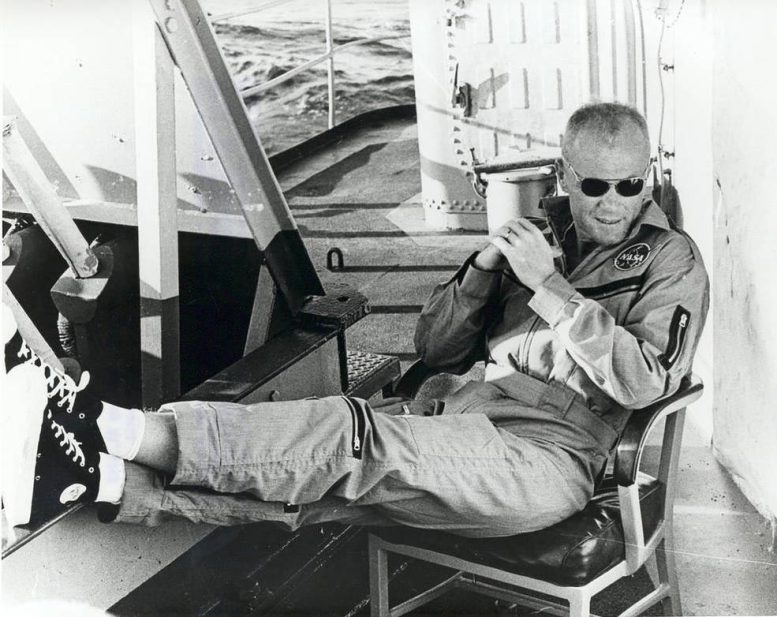

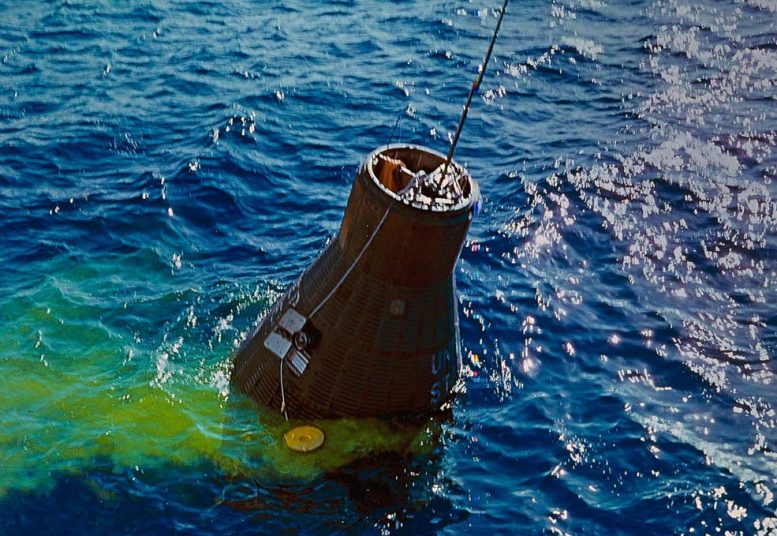

Friendship 7 splashed down at 2:43 p.m. EST about 800 miles southeast of Cape Canaveral in the vicinity of Grand Turk Island in the Turks and Caicos Islands, after a flight lasting 4 hours, 55 minutes, and 23 seconds. The U.S. Navy designated the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Randolph (CVS-15) as the prime recovery ship, but because Friendship 7 landed 41 miles west and 19 miles north of the planned splashdown target, the closest vessel, the destroyer U.S.S. Noa (DD-841), completed the retrieval from the water. Sailors aboard Noa spotted Friendship 7 descending on its parachute from an altitude of 5,000 feet and at a distance of about six miles. The Noa pulled up alongside the capsule, maintaining radio contact with Glenn throughout the recovery operation that took 21 minutes from splashdown to placing the capsule on the ship’s side deck. Sitting in the hot capsule, Glenn blew the side hatch, preferring that route of egress over the more difficult overhead hatch. After his egress, a team of doctors escorted Glenn to the ship’s sick bay where he removed his spacesuit, took a much-needed shower, and underwent a brief medical exam that showed him to be slightly dehydrated but otherwise in excellent physical condition. He ate his first food, other than the infight tube of applesauce, since breakfast early that morning. Wearing flight overalls, Glenn returned to inspect his spacecraft and awaited a helicopter to fly him to the Randolph.

Astronaut John H. Glenn relaxes aboard the U.S.S. Noa awaiting his helicopter ride to the U.S.S. Randolph. Credit: NASA

The helicopter from the Randolph hovered over the Noa’s deck and hoisted Glenn aboard. The helicopter delivered Glenn to the carrier where he received a more thorough physical examination by a team of Navy doctors, who also declared him fit and healthy. Glenn was then flown to Grand Turk Island, arriving there about five hours after splashdown. After another medical exam, Glenn finally went to sleep, more than 23 hours after awakening that morning for his historic day.

Astronaut John H. Glenn being hoisted onto a helicopter for the short flight from the U.S.S. Noa to the prime recovery ship, the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Randolph. Credit: NASA

Glenn spent the next two days on Grand Turk Island, undergoing more thorough medical examinations by the same team of physicians who examined him before flight. He also began his postflight engineering debriefings. Five of his fellow Mercury astronauts joined him on Grand Turk Island. In the predawn hours of February 23, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson arrived to pick up Glenn for the flight back to the United States. Despite the early hour, a large part of the local population turned out to see Johnson and Glenn. They arrived at Patrick Air Force Base (AFB), near Cape Canaveral, later in the morning. Glenn’s wife Annie and their two children, David and Lynn, met him at Patrick.

From Patrick AFB, the Glenns and Vice President Johnson motorcaded up the coast to Cape Canaveral, participating in a parade through Cocoa Beach. At Cape Canaveral’s Skid Strip, they met President John F. Kennedy who had just arrived. Glenn now rode in the Presidential limousine to Hangar S, where President Kennedy presented him with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal. Glenn responded with his usual humility, “I would like to consider I was a figurehead for this whole big, tremendous effort, and I am very proud of the medal I have on my lapel.” They then visited the MCC, where Flight Director Kraft and astronaut Shepard provided a tour, and LC-14, where Glenn presented the President with a hard hat worn by the launch pad workers.

Friendship 7 astronaut John H. Glenn, right, rides in a motorcade through Cocoa Beach, Florida, with his wife Annie and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. Credit: NASA

The Friendship 7 capsule also returned to Cape Canaveral. The U.S.S. Noa brought it to the shores of Grand Turk Island, placing it on a small boat that delivered it to a dock at the port. From there, workers trucked it to the airport and placed it on a U.S. Air Force cargo plane that flew it to the Skid Strip. Glenn and Friendship 7 were reunited at the event at Hangar S, where President Kennedy had a chance to peer into the recently-returned spacecraft.

President John F. Kennedy peers inside Friendship 7 as astronaut John H. Glenn looks on. Credit: NASA

On February 26, Glenn and his family traveled to Washington, D.C., where they attended a reception at the White House hosted by President Kennedy. Despite the rain, thousands turned out to see them as they rode in a motorcade with Vice President Johnson to the U.S. Capitol, where Glenn addressed a Joint Session of Congress. Later in the day, they attended a dinner in their honor at the State Department, where dessert featured Mercury ice cream.

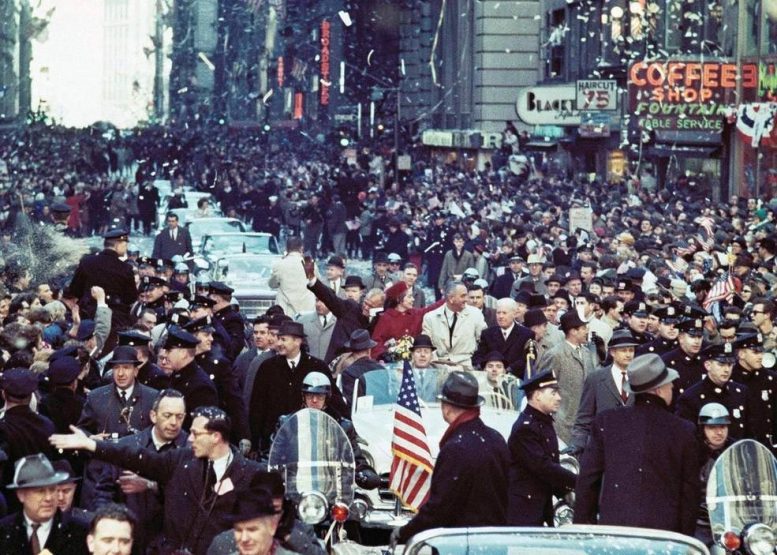

Friendship 7 astronaut John H. Glenn, accompanied by his wife Annie and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, during the ticker tape parade in New York City. Credit: NASA

On March 1, accompanied by Vice President Johnson, the Glenns took part in a parade in New York City, where police estimated four million people turned out to see them, throwing a record amount of ticker tape. Glenn gave a speech at City Hall, attended several receptions, and received several awards including the City of New York Medal of Honor. He addressed an informal session of the United Nations. Two days later, the Glenns’ hometown of Concord City, Ohio, welcomed them with a parade and several special events.

Three months after its Earth orbital flight, the Friendship 7 capsule began its next mission, popularly known as its “fourth-orbit tour.” The U.S. Information Agency and NASA organized a three-month round-the-world tour that took it to more than 20 countries, including all that hosted a NASA tracking station. An estimated four million people saw it in person and 20 million more on local television programs. A U.S. Air Force C-130 cargo plane emblazoned with the words “Around the world with Friendship 7” transported the spacecraft to the various locations, beginning in Hamilton, Bermuda, on April 20, 1962, through Latin America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Following its fourth-orbit tour, on August 6, 1962, the famous spacecraft went on temporary display in the NASA exhibit hall at the Century 21 Exposition, also known as the World’s Fair, in Seattle.

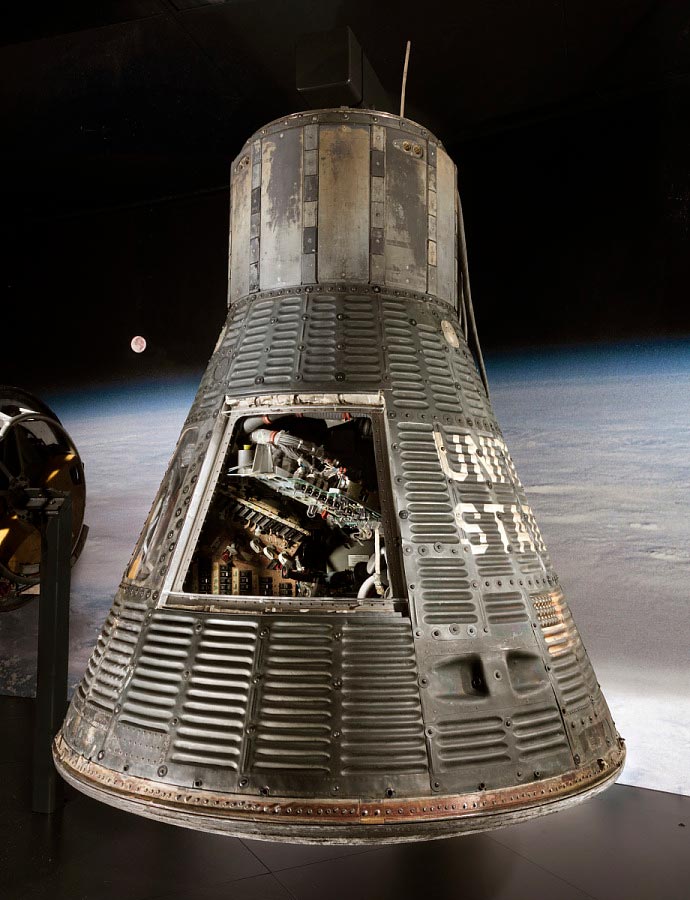

The Friendship 7 spacecraft is currently on display at the Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Chantilly, Virginia. Credit: Courtesy of NASM

On February 23, 1963, NASA formally turned the spacecraft, along with Glenn’s spacesuit and other artifacts, over to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where it has resided ever since. It is currently on display at the Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia. As far as Cape Canaveral’s MCC, although the building housing it was demolished in 2010, the control room was removed, relocated, and painstakingly restored, and is on display in the Kurt Debus Conference Center at the Visitors Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A full-size replica of Friendship 7 is on display at the entrance to Jags McCartney International Airport on Grand Turk Island, where officials renamed the main entrance road John Glenn Drive.

Enjoy a video of the Friendship 7 mission. (Produced 10 years ago for the 50th anniversary.

“Extreme travel lover. Bacon fanatic. Troublemaker. Introvert. Passionate music fanatic.”

More Stories

Your horoscope for Thursday, April 25, 2024

NASA's advanced solar sail successfully deployed in space: ScienceAlert

What Matty Healy's mother says about Taylor Swift's TTPD