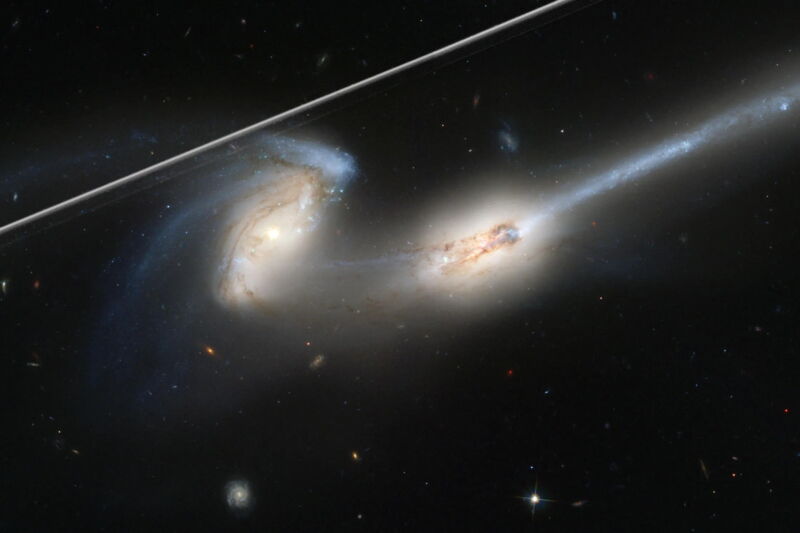

Space Telescope Science Institute; NASA

Swarms of satellites dot the Hubble Space Telescope’s field of view, leaving what look like scratch marks on space images and hampering scientists’ work. hustle swarms of these satelliteswhich reflect sunlight and mimic astronomical bodies, are gradually threatening Transforming the night sky And it affects how astronomy works.

David Stark, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said last week at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore American Astronomical Society Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In fact, he said, his team used a new detection method to measure the rate of satellite tracks double. But Stark was pitching his team’s idea to fix Band-Aid: a new program described in a file Modern report This is five to 10 times more sensitive at finding tracks than previous programs, and then hiding them. “It’s particularly good at finding trails of satellites that might otherwise miss,” he said.

It’s standard procedure for astronomers to try to clean up images of “artifacts,” such as the effects of cosmic rays hitting Hubble’s camera detectors, or diffraction spikes, which make bright stars look like crosshairs. Occasionally, a pesky Milky Way star might get in the way of one’s view of a distant object. The new technology, called Median Radon Transform, scans every linear path through the image at every possible angle. When a given path is aligned with a satellite path, the system notices a deviation from the mean flux—or brightness at a given wavelength in pixels—measured across regions of seemingly empty sky. It can also detect short lines, but they need to be a bit brighter for them to be selected, since they cover fewer pixels.

This software then allows astronomers to mask the satellite tracks, so that affected pixels are ignored in their analysis of the data. It’s like knocking over a few misprinted pages in a book, so you can skip them while you study the rest of the volume.

But it is better not to lose those pages. When there are multiple exposures of the same field, the astronomer can use additional software tools to completely remove the line from the final combined image. This part of the sky will then appear as it should, although the signal-to-noise ratio of the pixels in this line will be lower than if the satellite had not crossed in front of the telescope that day. Stark and his team include their code in a standard software package called “Extools” that they run.

However, this fix has a major limitation: It’s designed for the Hubble telescope, which orbits 332 miles above Earth, and is less exposed to satellite streaks than observatories on Earth. Terrestrial optical telescopes with wide-field imaging — which often don’t require multiple exposures — are likely to be more affected. There have already been a few instances of optical imaging satellite images being taken by telescopes Cerro Tololo Pan American Observatory in Chile and Lowell Observatory In Arizona, for example.

The problem will be much worse for the long-delayed National Science Foundation-funded project Vera Rubin Observatory, which is being assembled in the Chilean Andes and will start taking pictures next year. Its incredibly sensitive camera will detect faint, variable objects, such as a star going supernova or a near-Earth asteroid, and the telescope will automatically send alerts to astronomers when it detects such objects. But Robin cooperated Expressed concern On the possibility of false alerts thanks to light reflecting off satellites or unwanted space in orbit, he warned that up to 30 percent of his images could be affected by satellite streaks. For example, a gleam of sunlight from a small piece of insulation from a satellite seen in a telescope can appear like a glowing star. Unless the astronomer can also measure the spectrum of light, they might be fooled, says John Barentine, an astronomer in Tucson, Arizona, who recently He authored a monograph About light pollution from low Earth orbital objects.

The second problem is that the number of satellite lines is increasing. Stark tested the program on 20 years of data from Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys. While the satellite tracks did not change in brightness, it nearly doubled in rate. The team found traces in every three to four hours of Hubble data taken in 2002. But in 2022, Hubble satellites bombarded with light every one to two hours. This means that 5 percent of photos taken 20 years ago were affected, now it’s about 10 percent.

The rate will certainly continue to rise, says Sandor Crook, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Munich, Germany. “You would expect, over time, more streaks in the images. It is proportional to the number of satellites over the observatory,” says Kroc, lead author of a A recent study that used crowdsourcing labels and machine learning to track satellite paths in the images.

Kroc and his colleagues note a lower rate, rising from about 2.5 to 5 percent over the past two decades. They found that this trend escalated rapidly starting around 2018, around the same time companies began circulating Space mega constellations, connecting hundreds or thousands of them into networks. (Stark and Crook attribute the different percentages in their study to the use of different measurement techniques.)

These mega towers have clear benefits for their operators. Satellites are smaller and therefore cheaper to produce and launch, and networked services are less susceptible to disruption, such as via space climate or Anti-satellite weapons. SpaceX’s Starlink makes up the largest satellite network to date, with about 4,000 in orbit and plans to increase that to 42,000. The OneWeb constellation contains more than 600 satellites, but they are in a higher orbit, which reduces the impact on astronomical observations. And Amazon is preparing to launch its Project Kuiper this summer, flying its first satellites to provide broadband services on the inaugural flight of the United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket. The company plans to populate this constellation with more than 3,000 satellites.

SpaceX and some other companies have tested possible solutions, such as covering a satellite with a thin film to darken it so it reflects less light, or adding a visor to reflect light away from Earth. These limited efforts were far less than International Astronomical Union brightness targetsSome of these designs have caused problems for the satellites themselves, by heating them up too much or interfering with communications between satellites.

NASA

NASA’s concept of working with its commercial partners Hubble enhancement To a higher orbit may inadvertently mitigate the photodetonation problem. Atmospheric drag gradually pulled the spacecraft closer to Earth. Pushing it back is intended to extend its life — but it will also keep it away from a small fraction of passing satellites.

None of that will solve the problems of ground-based observatories, which have to look across the entire atmosphere, including all satellite orbits. And Barentine fears that although the companies haven’t found any technical fixes yet, they haven’t slowed the pace of satellite launches. “People in the industry have such a strong belief in innovation,” he says, “and my response to that has been this: The history of science, technology, and the environment is just full of head-on launches in technology that we didn’t understand created a lot of negative side effects.”

This story originally appeared wired.com.

“Extreme travel lover. Bacon fanatic. Troublemaker. Introvert. Passionate music fanatic.”

More Stories

A review of Rhengling at Erfurt Theater

MrBeast Sued Over 'Unsafe Environment' on Upcoming Amazon Reality Show | US TV

A fossilized creature may explain a puzzling drawing on a rock wall.