Balanophora is a parasitic plant that uses other people’s cells to build its own body.

It is known that many parasitic plants arose during the extreme period from the Cretaceous to the Paleogene, when dinosaurs became extinct.

The giant meteorite impact caused severe damage not only to dinosaurs but also to plants, causing the extinction of many plant species.

During this time, it is believed that some plants that were not able to survive on their own began to become parasitic on other plants.

Instead of delving deep into the ground and manufacturing nutrients from light, it was better to steal nutrients from the bodies of their comrades.

Animals and plants alike will do whatever they can to survive.

Since then, new parasitic plants have appeared every time the country goes through difficult times.

(*Parasitic plants are thought to have generated independently 12 to 13 times.)

The degree of dependence of parasitic plants on their hosts varies greatly depending on the species, from those that steal a small amount of nutrients and then photosynthesize on their own to complete parasitism (holistic parasitism) that is completely dependent on the host for all nutrients.

One common way nutrients are stolen by parasitic plants is by inserting thin protrusions called haustoria into the host’s body.

You could say it’s the way of sticking a straw in someone else’s shake and sucking it without permission.

But a group of parasitic plants called Balanophora use a very strange method of stealing.

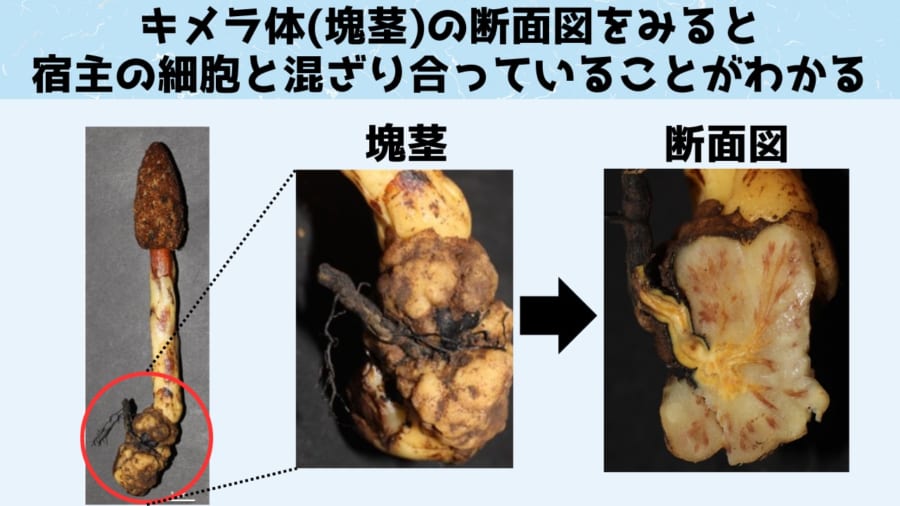

Balanophora pulls the host’s roots into its body and creates a chimeric body (tuber) which is a mixture of the host’s cells and its own cells, as shown in the diagram above.

When the chimera was cut into rings, it was confirmed that the host roots were mixed with Balanophora cells, and that they were stimulating the vascular system of the host plant.

The large body of the chimera (tuber) acts as a “food storehouse”, and Balanophora feed by absorbing nutrients from the body of the chimera (tuber).

In this case, again using the orgasm analogy, Palanovora does not impudently stick the straw into someone else’s orgasm and say: “I’d like to have some”, but rather says: “What’s yours” “is mine”, as if he were buying a shake he bought another person. It could be said that the entire container was taken away.

In both cases, the shake (nutrients) are still absorbed, but the Balanophora method uses the host’s cells to create parts of its own body, thus advancing the level of parasitism. You can say that it is in a state of existence.

However, as a general rule for parasites, it is known that the higher the level of parasitism, the more its body parts and genes are lost.

For example, Henegya Salminicola, a parasitic animal that parasitizes on jellyfish, was an animal with complex functions, but due to its long-term parasitic life, it lost all its body parts.

Furthermore, it is believed that they are no longer multicellular organisms and are in the process of evolving back into unicellular organisms.

For the first time a “reverse evolution” into monocytes has been reported!? A multicellular animal that “does not breathe.”

In addition, the “loss” of Heneguya Salminicola extends to the interior of the cell, and it has lost its mitochondria, making it dependent on the host even for oxygen respiration.

As a result of the parasitism, the mitochondria and chloroplasts inside our cells are purged of all functions necessary for single-celled organisms, and they eventually cease to be living organisms.

Ironically, the ultimate form of parasitism, chosen for survival, is the cessation of life.

“Travel maven. Beer expert. Subtly charming alcohol fan. Internet junkie. Avid bacon scholar.”

![[Windows11]WindowsUpdate May 2024 – Security Update KB5037771 error information[التحديث 1]](https://www.nichepcgamer.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/windows11-windowsupdate-exclamation.png)

More Stories

[Windows11]WindowsUpdate May 2024 – Security Update KB5037771 error information[التحديث 1]

German Mini Walk Map “Pikmin Bloom” Released!! Trandeco offers and interesting outdoor events guide[Playlog #627]|. Famitsu application[موقع معلومات ألعاب الهاتف الذكي]

ASCII.jp: The first TV product! Dolby Atmos(R) compatible for “Apple Music” “3 Months Free Apple Music Campaign” implemented