Geophysicists use seismic data from NASANASA's InSight probe has discovered a large underground water reservoir on Marsperhaps enough to fill the ancient oceans.

This reservoir, trapped within the middle crust of Mars, suggests that the Red Planet's water did not escape entirely into space but was absorbed into its crust, changing previous theories about Mars drying up and perhaps providing a habitat that could support life.

Using seismic activity to explore the interior of Mars, geophysicists have found evidence of a large reservoir of liquid water underground — enough to fill oceans on the planet's surface.

Data sent back by NASA's InSight probe has allowed scientists to estimate how much groundwater could cover the entire planet to a depth of one to two kilometers, or about a mile.

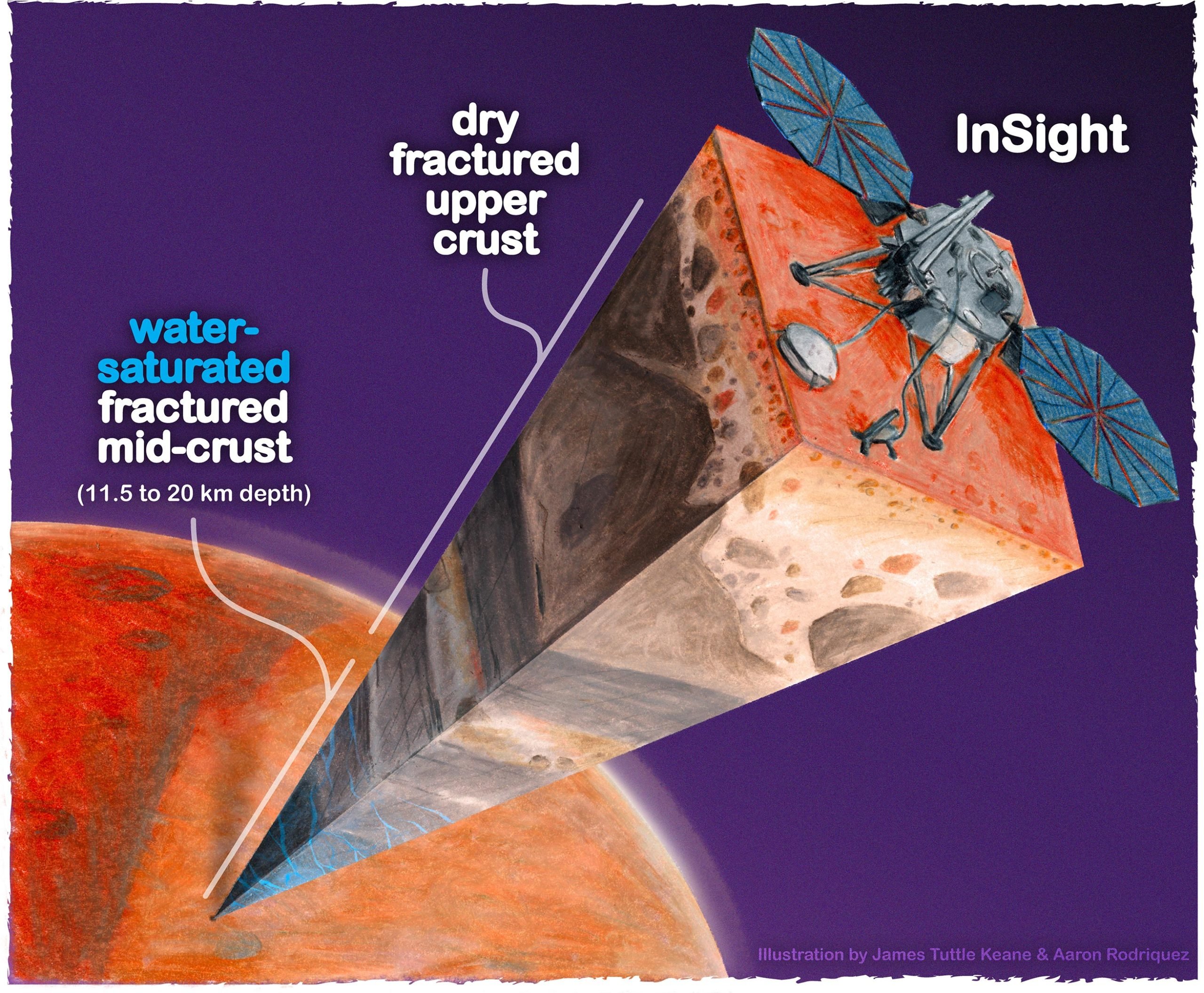

While that’s good news for those tracking the fate of the planet’s water after its oceans disappeared more than three billion years ago, the reservoir won’t be of much use to anyone trying to tap it to supply a future Mars colony. It’s located in tiny cracks and pores in the rocks in the middle of the Martian crust, between 11.5 and 20 kilometers below the surface. Even on Earth, drilling a hole a kilometer deep is a challenge.

Implications of Mars Colonization and Astrobiology

However, the discovery points to another promising place to look for life on Mars, if the reservoir can be reached. For now, the discovery helps answer questions about the planet's geological history.

“Understanding the water cycle on Mars is critical to understanding the evolution of the climate, surface and interior,” said Fashan Wright, a former UC Berkeley fellow who is now an assistant professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. “A useful starting point is to determine where and how much water is present.”

Wright, along with colleagues Michael Manga of the University of California, Berkeley, and Matthias Morsfeld of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, detail their analysis in a paper that will appear this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Techniques and Theories: Uncovering the Secrets of Martian Geology

The scientists used a mathematical model of rock physics, similar to those used on Earth to map aquifers and oil fields, to conclude that the seismic data from InSight could best be explained by a deep layer of fractured igneous rocks saturated with liquid water. Igneous rocks are hot, cooled magma, like the granite in the Sierra Nevada.

“The evidence of a large reservoir of liquid water provides some window into what the climate was or could be like,” said Manga, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Berkeley. “And water is essential to life as we know it. I don’t see why [the underground reservoir] “Mars is not a habitable environment. That’s certainly true on Earth – deep mines host life, the ocean floor hosts life. We haven’t found any evidence of life on Mars, but we’ve at least identified a place that could, in principle, support life.”

Manga was Wright's postdoctoral advisor. Morsfield, a former postdoctoral fellow in the mathematics department at UC Berkeley, is now an associate professor of geophysics at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Evidence of ancient water and geological evolution of Mars

Manga points out that a lot of evidence—river channels, deltas, lake sediments, and rocks that have been altered by water—supports the hypothesis that water once flowed on the planet’s surface. But that wet period ended more than three billion years ago, after Mars lost its atmosphere. Planetary scientists on Earth have sent probes and rovers to the planet to find out what happened to that water—water frozen in Mars’ polar ice caps can’t explain it all—as well as when it happened, and whether life ever existed.

The new findings suggest that a large amount of water did not escape into space, but rather into the Earth's crust.

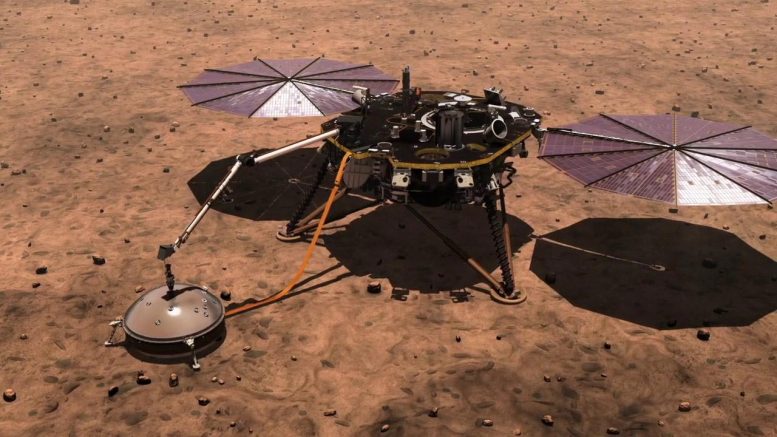

NASA sent the InSight probe to Mars in 2018 to investigate the crust, mantle, core and atmosphere, recording invaluable information about the Martian interior before the mission ends in 2022.

“The mission has greatly exceeded my expectations,” Manga said. “By looking at all the seismic data that InSight has collected, they have been able to determine the thickness of the crust, the depth of the core, the composition of the core, and even a little bit of the temperature inside the mantle.”

The InSight spacecraft has detected earthquakes on Mars measuring up to magnitude 5 on the Richter scale, meteorite impacts and rumbling volcanic regions, all of which have produced seismic waves that have allowed geophysicists to explore the planet's interior.

A previous study suggested that the upper crust above about five kilometers contains no water ice, as Manga and others suspected. This may mean that there is very little accessible groundwater ice outside the polar regions.

The new research analyzed the deep crust and concluded that “the available data are best explained by a water-saturated middle crust” beneath InSight’s location. Assuming the crust is similar across the planet, the team argued that there should be more water in this middle crust region than “the amounts suggested to fill the hypothesized ancient Martian oceans.”

To learn more about this discovery, see Did We Just Find Liquid Water on Mars? Stunning Data from NASA's InSight Rover.

Reference: “Liquid Water in the Middle Crust of Mars” August 12, 2024, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.2409983121

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Office of Naval Research.

“Extreme travel lover. Bacon fanatic. Troublemaker. Introvert. Passionate music fanatic.”

More Stories

A fossilized creature may explain a puzzling drawing on a rock wall.

MrBeast Sued Over ‘Unsafe Environment’ on Upcoming Amazon Reality Show | US TV

Watch comets Lemmon and SWAN approach Earth today