When Barack Obama asked for a poem from Elizabeth Alexander at his first inauguration, political journalist George Packer commented on it. The New Yorker: The president-elect should abstain from his idea, because Alexander’s poems showed the fatal characteristics of contemporary American poetry, “a personal definition and not very universal, with moves toward the general, not academic.” Even if Packer is not noticed by an extravagant reading of poetry until then, poet Ben Lerner agrees: “The fatal problem of poetry: poetry.”

“Why do we hate poetry?” Asks Ben Lerner in his article The Bad Dialectic. George Packer had to serve those who hated the poem “nostalgia” who believed: there was a poet who could “through the magic of language and performances” create an individual self that represented the masses and spoke on behalf of everyone at the same time.

As naive as this idea sounds, Lerner sees the avant-garde as a savage, which considers the poem “an imaginary bomb with a real shrapnel” that deconstructs poetry and penetrates future history. Lerner’s brief response to both camps: The poem remains a poem. It cannot speak for everyone, and it is confined to the forbidden art zone, it is not suitable as a revolutionary weapon. A concrete poem is always only “an echo of a poetic possibility,” so it is always elegiac.

Ben Lerner: Why do we hate the lyric? article. Translated from the English by Nicholas Stingle. Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2021, 100 pages, 14 €.

Ben Lerner became famous in Germany last year for his third novel, “The Topeka School”. He uses literary means to analyze diseases of public speaking and describes how the collective psyche breaks down among them. Against the background of elections in the United States, he also aroused great interest in this country. With the new version of his article, Suhrkamp-Verlag now surrounds the elegantly furnished bilingual full version of Ben Lerner’s poems. It demonstrates how Lerner deals with questions of personal expression and public demands, poetic reasoning and political reference in lyrical practice.

Under the heading “Without Art”, the German edition collects volumes of poetry “Die Lichtenbergfiguren”, “Scherwinkel” and “Mittlerer frei Weg”. All titles refer to physical phenomena and declare it to be the poetic process. They have all been translated by poet and writer Stephen Pope, the Younger in collaboration with Monica Rink. Everything is framed by two programming poems, the last poem giving the title to the volume, as well as an excerpt from “Snow over Venice,” a collaboration between Alexander Kluge and Ben Lerner from 2018, which is transformed into an introduction. His presenter calls Cluj “the constellations,” and thus captures the way Lerner works: “Well, more pattern than planning is what I think of,” Lerner explains in an interview with Yale Review.

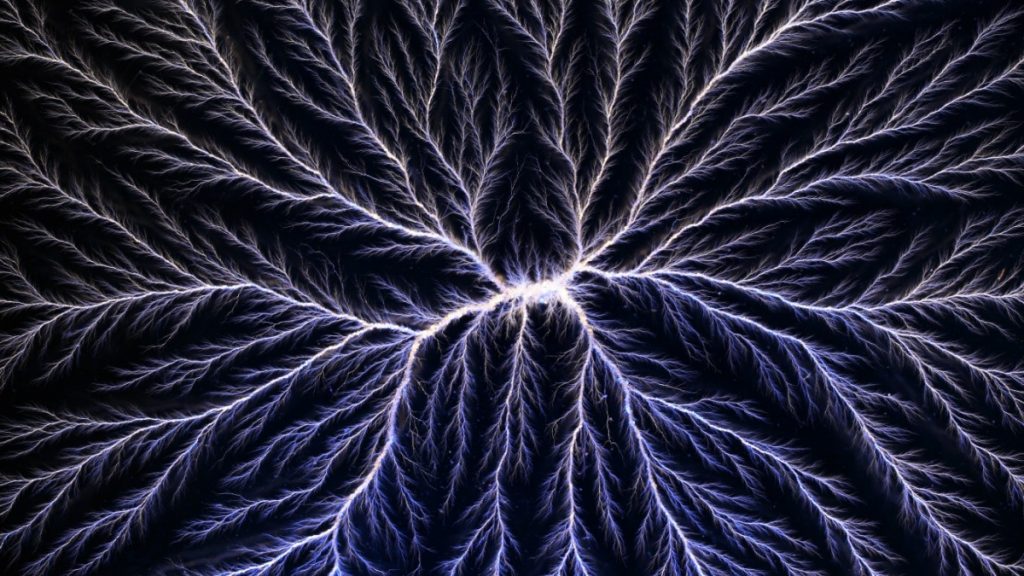

You can say that. Lerner’s peculiarity is in thinking of patterns and compositions rather than plans and lines more explicitly in “Die Lichtenbergfiguren”, the still outstanding first volume. The Lichtenberg characters are named after their discoverer, George Christoph Lichtenberg, and are the patterns that high voltage discharges leave behind. For example, on the skin of victims of lightning strikes.

Think Patterns Instead of Plots: The Poet, Ben Lerner.

(Photo: imago stock & people / imago / Leemage)

Steffen Popp explains it in the closing word, which also introduces the translation difficulties well. In a work journal published online, he describes how Lerner transformed the violence of a lightning bolt into a poetic process: “You look at the Sonnet engine room, which has had its popular user interfaces removed. Tied together with new machines, remnants of old user surfaces, and new surfaces, like panels Solar and carbon fiber, spanning blasted oak and steel beams. ” It might sound very strange: “Darling, my favorite natural abstraction is the tree / so if you see one off the highway think / snippet, that Latin box in which I keep the tilde / your name.”

When Ben Lerner shortens technical terminology from theoretical disciplines, everyday language, and cultural references in this way, when he shatters and recombines the images, the quiet moments in these reference thunderstorms are more evident: “Due to the nature of men, women fill snow in mugs for the summer.” Doesn’t this image sit in the poem as if in a Faraday cage while the abstractions revolve around it? Save behind bars, so to speak? Isn’t it the case that Ben Lerner is pouring the fog of his intellect into concealing classical poetic motifs under her protection? One could almost say: Not only poetic motifs, but about human existence.

“Night, sleep, death and / the stars” is erased and summoned in the opening poem “Directory of Subjects”, a poem whose verses are arranged around a clearly defined vertical axis, as if two texts were joined to each other by a joint. Who talks about the poem and another talks about love. “Collective despair phrased in sentences in the first person” in the face of traditions that no longer mean anything and can no longer generate warmth. But without warmth – what then is the poem, who is its author, and who is its reader?

Ironically, the uncharacteristic exclamation is: “People for the sake of God. Open your hearts.”

At one point in his book “Passagenwerk”, Walter Benjamin is surprised that people have agreed on a phenomenon that is so existential to them in their most vulgar conversations: the weather. Benjamin writes: “What a beautiful, ironic connection to this behavior in the story of the twisted Englishman who wakes up one morning and shoots himself because it is raining.” The paradox in the story is clear: conversations about the weather protect against the cruelty with which we live at the mercy of cosmic powers. But at the same time, there is something very violent about how to deny reality in this way.

What Benjamin is the weather, the learner is the language. The poem is like a conversation about the weather and talking about the weather like Faraday’s cage preserves him, but also prevents him from exposing himself to his conditions of existence. So the title of the entire volume “No Art” is perhaps more of a wish than an assertion. Wanting to get out of the cage and knowing that this is impossible: “I see myself as part of a people, / a small people, in a state / failure, and in love // more avant-garde than shame.”

There you have it: the elegy gesture. He does not mean anything from the past, but rather the poem as “an impossible character for him.” This echoes when the second volume, “Scherwinkel”, ends with the satirical exclamation pointless: “People for the sake of God. Open your hearts.” It resonates when Lerner asks about national myths and in the long poem, “The Lamentation of Education,” dealing with the events of September 11th, he comes to the conclusion that only denial of meaning can “explain this event with love,” that is, respond with sadness to violence.

Ben Lerner: No art. Poems. Poems. From American English by Steffen Popp in collaboration with Monika Rinck. Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2021, 512 pages, 34 €.

Its resonance reverberates when Ben Lerner also criticizes the change in public discourse in his poems and leads to his rhetorical movements within static prose blocks: “We say vertically arranged texts address audiences, when in reality they cannot convey the humility necessary for the life of society to assemble a narcissistic crowd.”

The way Ben Lerner demonstrates his poetic dilemma, but also a social dilemma through his lyrical “structural experiences”, and how Steffen Popp also found decisive equivalents to these crucial poems in German in his collaboration with Monika Rinck, makes an impression. Ben Lerner does not believe in the idea of the poem as a magic pill that changes everything. In literature one cannot help but dream of such a language. The year is also a fiction, Lerner quotes a statement by poet Claudia Rankin in his essay. But it is raised, negatively, in the poem, in the cage that saves you, but you cannot get out of it.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

“Crackhead Barney” says she was mutilated by Alec Baldwin

We may have detected the first magnetic flare outside our galaxy

Lost Gustav Klimt painting sold at auction