This scenario re-emerges as a real possibility in recent economic data.

Written by Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

When the Fed cut interest rates on September 18, it looked at labor market data that showed job creation surprisingly slowing to weak levels, decent consumer spending data, median income growth, and very little and declining savings. an average. The trends seemed poor.

But 11 days after the Fed's decision, revisions and new data arrived. The whole scenario changed.

So, at the summary level, economic growth in three of the past four quarters, as revised, has been well above the 10-year average of about 2.0% for inflation-adjusted GDP growth:

- Q3 2023: +4.4%

- Q4 2023: +3.2%

- Q1 2024: +1.6%

- Q2 2024: +3.0%

And the third quarter looks good, too: The Atlanta Fed's estimate for third-quarter real GDP growth is currently 3.2%, of which consumer spending contributes 2.2 percentage points, and nonresidential fixed investment contributes 0.9 percentage points.

Regarding the hurricanes and tornadoes that caused so much destruction and terror: As job sites were temporarily closed and people had difficulty getting to work, there would be a temporary spike in weekly unemployment claims and a slight increase in unemployment in the affected areas. But the United States has experienced the horrors of hurricanes and tornadoes several times. What then quickly follows is a spending and investment boom from cleanup, replacement, and rebuilding, all of which contribute to employment and economic activity.

A set of huge revisions after the Fed meeting.

Consumer income, saving rate, spending, gross national income, and gross domestic product It was revised upward on September 27, 11 days after the Fed met to cut interest rates.

The annual revisions to consumer income and savings rate were huge this time, going back to 2022, and consumer spending was also revised, but not as much.

These massive revisions to income and the savings rate solved the puzzle: why consumers held up so well. They succeeded in bringing the growth of GDP and GNI back to straight by adjusting the growth of GDP slightly higher and raising the growth of GNI a lot.

The scale of the reviews has been staggering, and we speculate here that the widespread influx of legal and illegal immigrants — which the Congressional Budget Office estimates at 6 million total in 2022 and 2023, plus more in 2024 — has finally been caught. Some data. A large portion of them have joined the workforce, and many of them work, earn money, and spend money, thus increasing their income and spending statements.

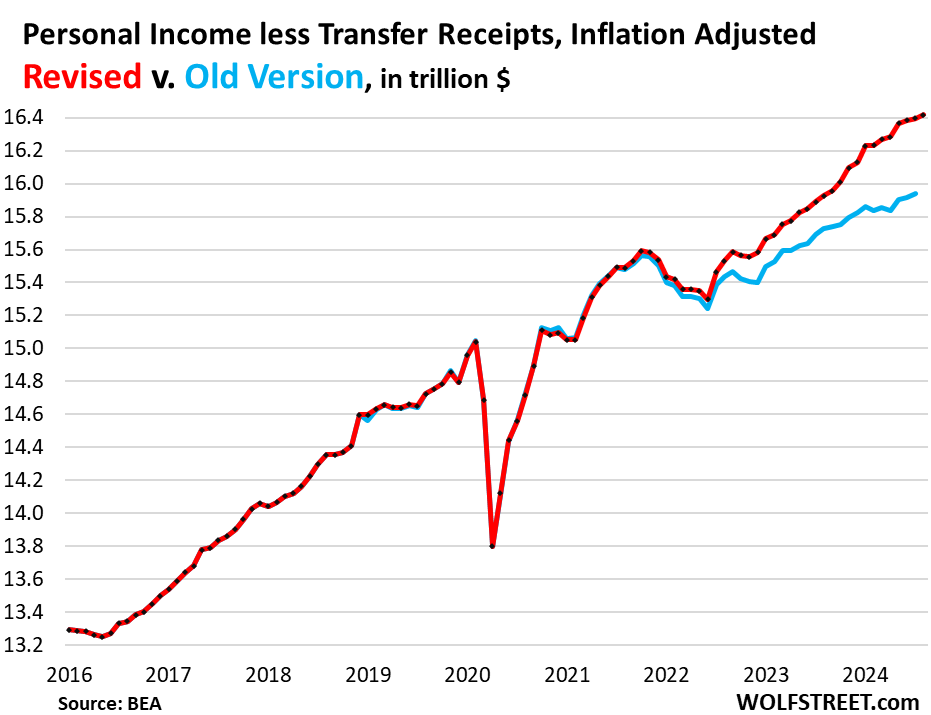

Between July 2022 and July 2024, during these two years, personal income without transfer receipts (and thus without payments from the government to individuals, such as Social Security, VA benefits, unemployment insurance compensation, welfare, etc.) was adjusted for inflation:

The savings rate revisions are important because they showed that consumers spent much less than they had through 2022 and saved the rest, which bodes well for future consumption.

Income was revised up significantly, spending was revised up but less, so the saving rate – the percentage of disposable income not spent by consumers – was revised in a striking way: the revised saving rate for July was 4.9%. . The old version of the savings rate for July was only 2.9%.

We have seen in inflated cash holdings, such as CDs, money market funds, and Treasury bills, that households are not only flush with cash, they continue to add to their cash holdings, and we have used this continuing inflation of cash holdings as a better proxy. A signal to consumers' health from a weak savings rate. Now these huge savings rate revisions going back two years have been confirmed.

Nonfarm payrolls data was revised upward On October 4, 16 days after the Fed meeting.

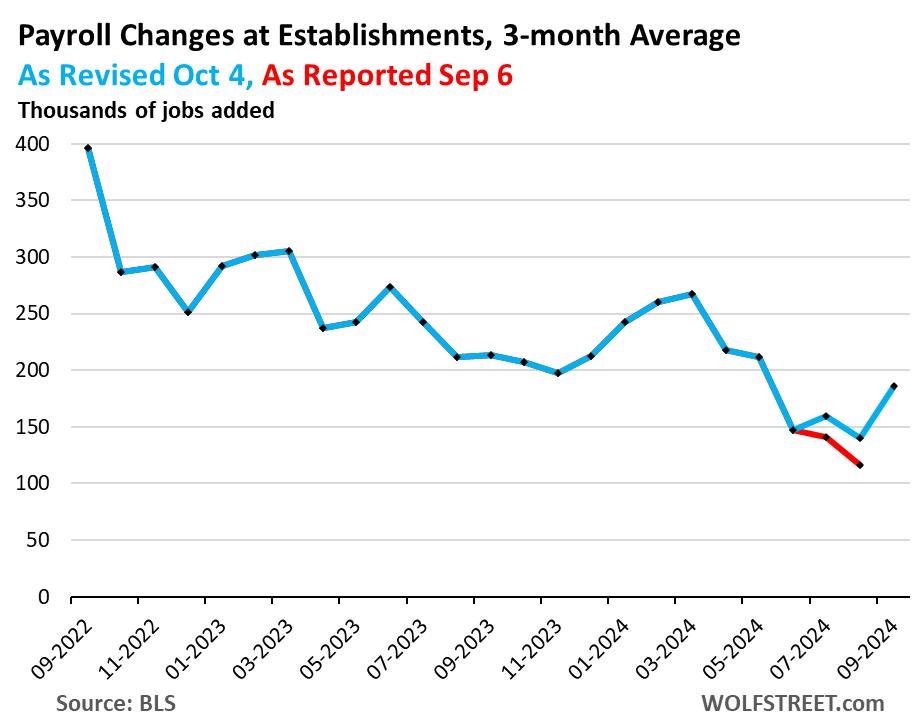

The main reason the Fed cited for the 50 basis point rate cut was the sudden deterioration in nonfarm payrolls data: the three-month average of jobs created slowed significantly in July and August, partly due to downward revisions to previous data. . We pointed this out at the time, and it was a disturbing scene.

But with September's strong jobs report came increasing revisions to previous data that prompted this headline here: OK, forget it, false alarm, the job market is fine, the bad stuff was revised last month, and wages jumped. No need for further interest rate cuts?

“Pandemic distortions and the sudden entry of millions of migrants into the labor market, who are difficult to trace, have significantly damaged the accuracy of the data,” we said in the subheading. There is no such thing as a data blow.

It also solved another mystery: The weak jobs data for July and August didn't match up with other employment data, which was fairly good.

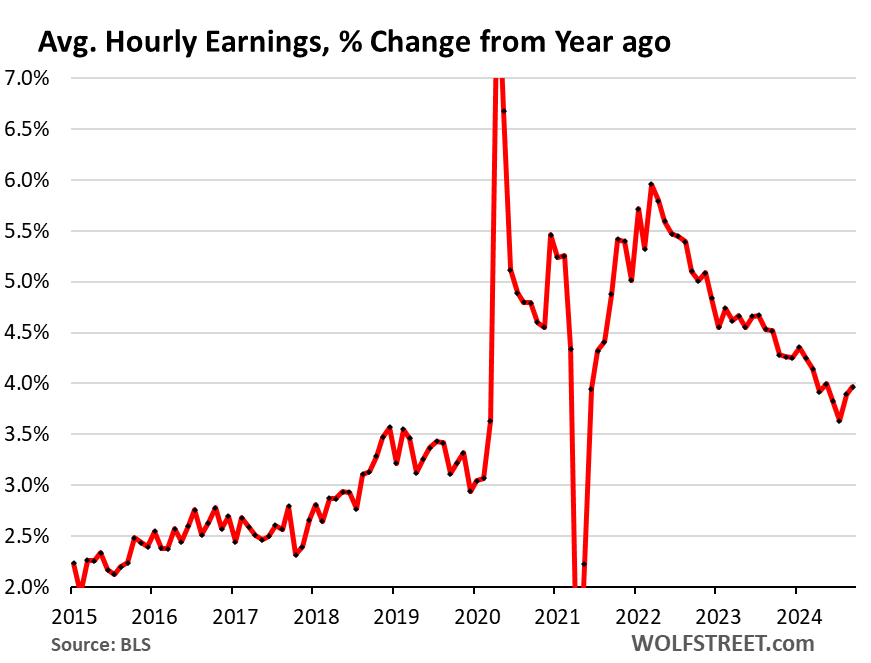

Hourly wage increases were also revised upward, with revised three-month average earnings growth rising to 4.3% year over year.

The year-over-year increase rose to 4.0% for September, the second consecutive month of year-over-year increases. Combined, these two months increased by the most during any two-month period since March 2022, and are well above the 2017-2019 peaks.

“So, in terms of inflation — and what the Fed was worried about — accelerating wage growth is no longer going in the right direction,” we said at the time.

Therefore, inflation is no longer moving in the right direction.

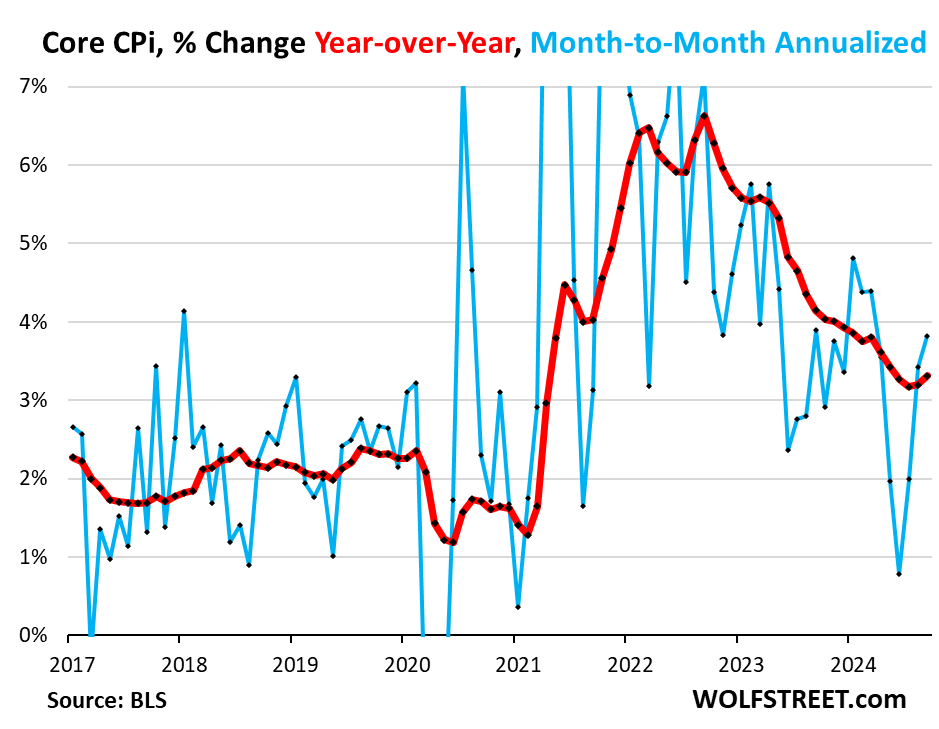

Energy prices have fallen, covering up problems beyond energy.

The core CPI, which excludes energy products and services as well as food, accelerated for the third straight month in September to +3.8% year-on-year (blue line), accelerating the 12-month rate to 3.3% (red line).

It has been shown that inflation in services remains constant. Then there are cars, where prices have fallen — the used-car decline — which has been a big factor in pushing the core CPI lower since mid-2022. But they turned around in September and are trending higher (for more details, see our article Under “Inflation whipped into the CPI.”

This is not as hot inflation as it was two years ago, it is much lower than that, and the Fed has been successful in bringing inflation down, but it is re-accelerating inflation that is still very high to begin with.

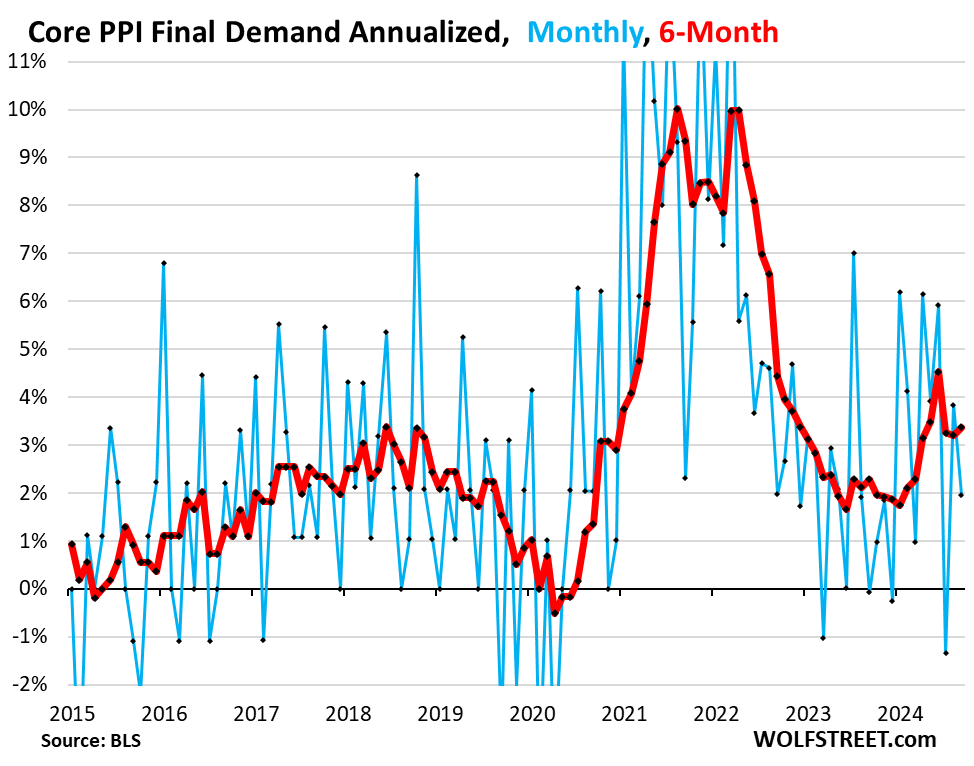

Inflation at the producer level – apart from the decline in energy prices – was heading in the wrong direction throughout the year, driven by an acceleration in inflation in services, after benign readings last year.

On Friday, the core PPI became much worse due to large revisions to previous months, causing the six-month average (red) to accelerate to +3.4% y/y for September. Last year, the index hovered well around the 2% line.

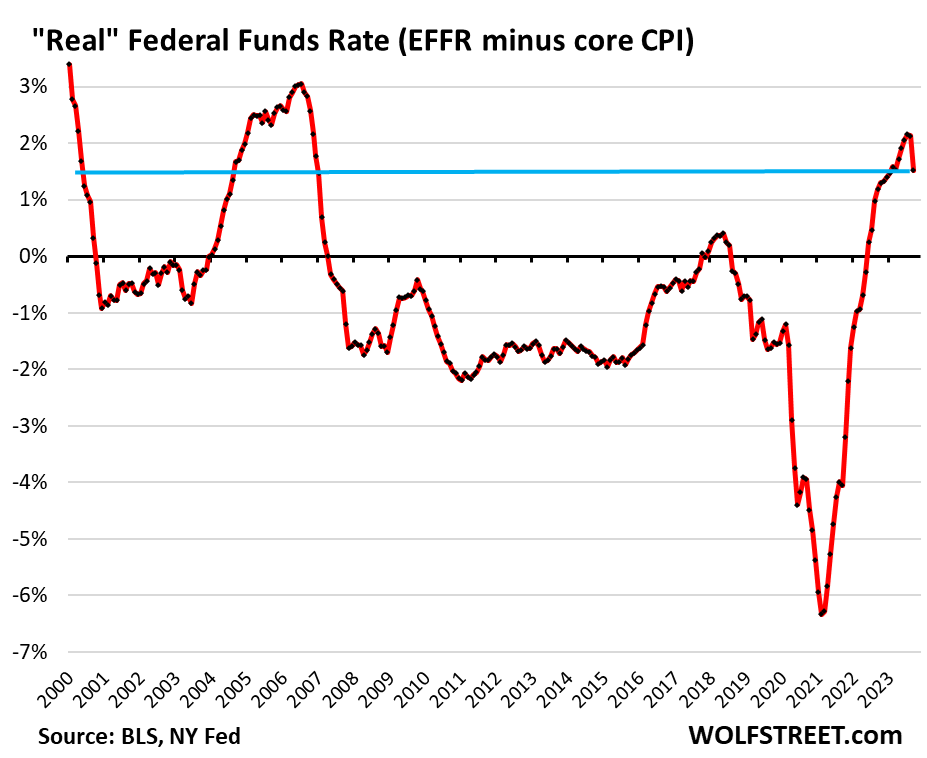

The Fed's interest rates are still well above inflation.

The effective federal funds rate (EFFR), which is the target of Fed interest rates, fell to 4.83% after the rate cut, about 1.5 percentage points above the 12-month core CPI inflation rate. The EFFR minus core CPI represents the “true” EFFR, adjusted for core CPI inflation.

The zero line indicates the point where the EFFR equals the core CPI. During the ZIRP era following the financial crisis, the real EFFR spent most of the time in negative territory. In 2021, as inflation exploded and the Fed was still near 0% with interest rates and doing $120 billion a month in quantitative easing, the real money flow rate historically fell deeply into negative territory. The Fed has described this phenomenon as “temporary,” and we have described the Fed as “the most reckless Fed ever” (google it, just for fun):

The Fed assumes that official interest rates that significantly exceed inflation are higher than some theoretical “neutral” rate and are therefore “constrained.”

Fed governors have differing opinions on where the neutral rate could be, as no one knows because it is just a conceptual rate, and therefore differing opinions on how restrictive current interest rates are – but they agree that they are, at least for some. end.

But what we see in the economic data is that official interest rates may not be so restrictive after all, and that the “neutral” rate may be higher.

However, the signals are mixed.

Some sectors were hit hard by those high rates, especially commercial real estate, which has been in the doldrums for two years. For CRE, which went into a frenzy during ZIRP, financial conditions are now stifling. But this may be useful in eliminating some of the excesses and re-pricing properties to where they make economic sense.

Manufacturing, after the boom in manufactured goods during the pandemic, was about to stabilize at a high level.

But other sectors are soaring and rising further, including consumers.

Ultimately, the dizzying bubble in AI led to a massive investment boom — from the construction of power plants and data centers — fueling insatiable demand for specialized semiconductors, spurring hiring and even office leasing, and spurring waves of corporate spending and investment. , and waves of venture capital investments in startups that use artificial intelligence in their descriptions. As for anything related to the AI bubble, interest rates appear to be quite stimulating.

Given the current level of inflation – 12-month core CPI at 3.3% – and where core interest rates were before the rate cuts – at 5.25% to 5.5% – it made sense to lower interest rates to bring them closer to inflation rates, but keep them higher. much higher inflation rates.

The media has declared victory over inflation, not the Fed.

The problem arises if inflation follows a steady path of acceleration. Powell and the Fed governors have pointed out this risk several times. They are fully aware of this danger. They worry that inflation is going in the wrong direction again and in a sustainable way. Inflation has been heading in the wrong direction in recent months, but for a sustained acceleration, we will need to see more bad data, given how volatile the data is, to identify a strong trend. They are wary of that. They did not declare victory and say so. But the media has declared victory over inflation, no matter what the Fed or the data says.

If there is an acceleration in inflation, the Fed could pause interest rate cuts for more wait-and-see. If the data received before the November meeting goes in this direction, waiting and seeing would be wise.

If a wait-and-see policy does not stop accelerating inflation, and if interest rates are not constrained enough to keep inflation low – a possibility that rises with every rate cut – the Fed could raise interest rates again. Interest rate cuts are not permanent. These scenarios are beginning to appear on the horizon again.

The current situation also suggests that higher interest rates may actually be good for the economy as a whole, especially in the long run, including why a higher cost of capital promotes better, more disciplined and more productive decision-making.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate that very much. Click on the beer and iced tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Register here.

“Extreme travel lover. Bacon fanatic. Troublemaker. Introvert. Passionate music fanatic.”

More Stories

Chinese company BYD surpasses Tesla's revenues for the first time

Dow Jones Futures: Microsoft, MetaEngs Outperform; Robinhood Dives, Cryptocurrency Plays Slip

The US economy grew at a strong pace of 2.8% in the last quarter thanks to strong consumer spending