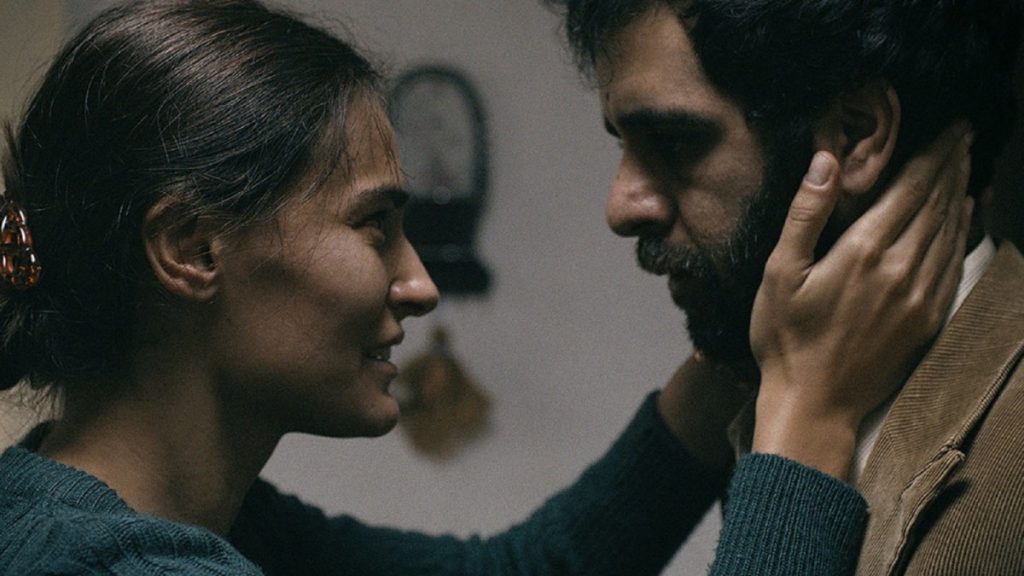

A cloud of noise and dust hangs over the Fikertepe district of Istanbul, where Kamel and his wife Ramziah live in one of the small houses. Some of the doors are covered with plastic sheets and they share the vegetable garden with their neighbours. Camille (Erol Afshin) does not have a job, Ramzia (Saada Aksoy) cleans the house of a wealthy woman. And she’s pregnant: When she has stomach cramps, Camille squeezes a damp cloth over her forehead and dreams of a future where he’ll add a children’s room to the house and they won’t have to worry. But Ramsey interrupts the imagination harshly: “You know they won’t let us live here.”

“They” are the cause of the noise cloud: the real estate investors who have already forced Camille’s friends out of their homes a few hundred meters away, which are now just rubble under the shovels of excavators. And soon men also knock on their doors, dreading Camille and Ramsey, the banknotes in their pockets and the offers they could not refuse. The noise of construction hangs in the air as a constant reminder: Soon it will all be over. You will be leaving soon, too.

A society in which human despair is despised

But Camille’s financial worries are so great that he takes a job at this very company. He drives excavators without a license and with less money than usual, because he took the job from the Syrian Ammar (Keddah Ramadan) after he injured himself. Workers at the construction site say the “Syrians” are undermining the wages that Turkish construction workers have negotiated and are working for little money. Kumail is now one of them: not Syrian, but his colleagues beat him with the same anger.

Everyone in “Saf” is angry anyway, mostly from Kamel, who sometimes seems to be the last good person in Istanbul in a society where despair has wiped out humanity. Angry allegory because her husband naively believes in the good, the neighbor because he works with the biggest enemy and does not water the vegetable garden properly, Amar because he wants to get his job back to feed his family.

Director and screenwriter Ali Vatancifer spins a vortex of despair and despair that deepens symbolism and wholeness deeper and deeper with extraordinary intensity. It’s a constant alternating between the lively dialogues, the words of others that attract the heroes, and the sheer exhaustion when they walk alone in the streets of the night.

You see people tearing each other apart

The Turkish word “pure” has several German translations: it can mean “original,” “pure,” “gullible,” or “gullible.” Or also: “Take a stand.” They have to take a stand, make decisions, the clean, the gullible, the gullible. Ramsey has to decide whether to slander her colleague in order to take on her job as a nanny in addition to the cleaning. Kamel, whoever he may be on his side, clings to his home and his employer. He has to get the money from somewhere to pay for the excavator license and not lose his hated job.

In the end, you see people tearing each other apart, even though they stand together on the edge. And he understands: Perhaps none of them can do well in a world where people are merely disruptive agents or tools of faceless investors.

juiceTurkey 2018 – Director and script: Ali Vatancifer. Camera: Theodor Vladimir Bandoro. Editor: Evren Lus. Casting: Erol Afshin, Saad Aksoy, Kida Khader Ramadan. True Fiction, 102 min. Theatrical release: February 24, 2022.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

A fossilized creature may explain a puzzling drawing on a rock wall.

MrBeast Sued Over ‘Unsafe Environment’ on Upcoming Amazon Reality Show | US TV

Watch comets Lemmon and SWAN approach Earth today