This book owes the amazement that was once considered, not wrongly, the beginning of all philosophy. How is it possible that one has not seen anything from all sides (the closet in the bedroom, for example, not from below) and yet with complete confidence claims that it must be summed up as a whole in one word, as it is all just right? And where’s the locker anyway? Does he stand outside in the room, where he belongs and we need, or perhaps not in our heads after all, where, as they say, our consciousness and all our experiences occur on our own? But where would the head be then? These questions are ancient and have been dealt with a lot, but to this day they have not lost their power to lead to Aporea after only a few steps.

Tim Parks, a novelist and cultural scientist from England who lived in Italy for a long time, aligned himself with his friend Riccardo Manzotti’s theory of a “diffuse mind”. This means that the ego and the world are not completely separate, as Kant claims, and that reality and experience are not all products of our 100 billion neurons, as is consistent with today’s brain science, but owe to the encounter and connection between them, subject and object. This is in fact so true and obvious that one does not fully understand how Parks became enlightened, nor why this theory meets such fierce opposition. It captures the obvious without wanting to explain it further, but it has a provocative quality.

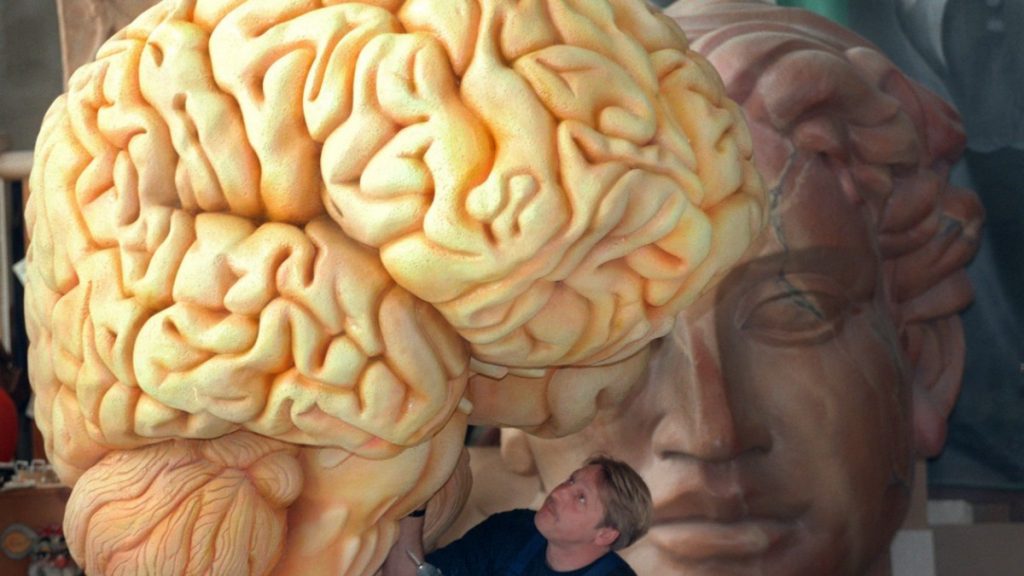

In this way he carries the spirit of subversion to the world of research

As part of a project aimed at promoting dialogue between the humanities and the natural sciences, Parks ends up in Heidelberg, where some of the world’s leading neuroscientists do their work. There Parks wanders the old town and has breakfast in the hotel with his Italian partner, who is only half his age, mostly under the gazes of the other guests; In general, this is, at least as far as the self and the brain are concerned, also a book on Anglo-Saxon experiences in the world of Kaiserschmarn and Echendorf, which sometimes gives it a somewhat teasing tone.

But if this is an aberration, it is deliberately discursive. Time and time again, Parks reassures himself when he visits the stars in this venerable science haven, his own unstructured experience. With his apparent naivety, he carries a subversive spirit in the research world. There he behaves like Inspector Columbo, who also tries to make sure that everyone underestimates him and, at most, views him as a pleasurable pain in the ass: that’s exactly how the culprits catch! Everyone greets him kindly and shows him their labs, because what they do is complicated but it is not a secret. He repeatedly emphasizes his lack of need, and he must have misunderstood something – no, no, he hears with care that he understood it all too well. In doing so, the gallows is secretly drawn.

The famous researcher working on facial recognition in children realizes that she is constantly using the words “code” and “represent” without being able to say what they actually mean; And he notices very precisely where the conversation with her really ends, and when she turns on “autopilot”. Thomas Fox, the advocate of “activation”, who insists that consciousness arises in an intentional relationship to the world, has no answer to the question of why so many things appear in our consciousness that we do not care about them at all, such a ceiling.

Tim Parks: Am I sane? On the road to awareness. Translated from the English by Ulric Becker. Kunstmann, Munich 2021. 303 pages, €25.

The core of the book is the critical anatomy of some scientific and popular representation, showing the entire subject how battered it is by conceptual loss of consciousness. With regard to consciousness in particular, there is a complete confusion: the ‘meta’ property is something that ‘comes’ – to express an explanatory value like ‘Ah!’ Loudly “Ah!” The sight of fireworks in the night sky. Consciousness drives scientists crazy, because there is a clear elementary phenomenon that at the same time turns out to be inseparable into its parts, as they used to dissect mouse brains. Then they produce uninformed sentences, which Barks takes piece by piece in order to arrive at the following result:

This last sentence is really unusual. These famous scholars first admit that they lack ‘verifiable’ theories of what consciousness is, but then immediately postulate that there is consciousness on the one hand and a ‘material substrate’ or ‘physical substrate’ on the other. of consciousness, indicating that consciousness itself No physical. This in itself amounts to a theory of consciousness and, moreover, an inevitably dualist theory.”

And they don’t notice it. Before this blindness, Sparks continues in a polite but deep astonishment. How can an intelligent person write a sentence like “Our brain tells us a story and we take it for granted, no matter what it looks like”? There must be an ‘we’ separate from the brain, which has just been left out in the assertion that the brain is a ‘narrative’ that is to say an entity subject to experience. Parks quotes longer passages from a work called Neuroscience for Dummies and concludes with the question of who the puppet really is here. For his standards this is very blatant.

But Parks is still very much so awake and self-defeating in victory. In the case of the unsatisfying discussion, he also sees a truce between two opposing needs of society: everything must be scientifically controllable – and yet people and their souls must remain our very exclusive secret. Because it saves us from having to make a decision, he says, we’re happy to pay the pricey, expensive dead end of this research.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

A fossilized creature may explain a puzzling drawing on a rock wall.

MrBeast Sued Over ‘Unsafe Environment’ on Upcoming Amazon Reality Show | US TV

Watch comets Lemmon and SWAN approach Earth today