What is the common denominator between a cinematograph and a sausage machine? When film producer William Selig visits the largest slaughterhouse in Chicago at the beginning of the twentieth century, a young man tainted in the butcher’s yard runs behind him and asks him to record the work of the sausage machine with his camera: there are no advertisements for Armor’s slaughterhouse, but please explain Lichtspiel’s new method about the production of armored sausages! Her secret recipe: “Take what’s on the washing shovel, including spit and sawdust, knead it with gristelle, bone meal and last year’s sausage, stir in borax and glycerin and push it through the machine. With mice, rat poison and anything else that has fallen into the funnel. For example, leather From the hands of the men in the processing hall. It explodes in brine. Oh – and did you know that stingray cattle are getting fat faster?”

“No,” answers Selig in Kristen Wonicki’s “Selig & Boggs,” which can now be read again in a particularly elegant new edition. “The play of light is enlightening the people for the future!” Oh, said Selig, the man hopefully.

Upton Sinclair can be identified in The Young Butcher, whose early vision of anti-capitalist and horrific pigs landed in The Jungle. On the other hand, the new medium of the film works in a similar way to the sausage machine. Swallow all the trash that makes no sense to culture or society. William Nicholas Selig had already walked across the American South in the 1890s and worked his way from house mechanic to prodigy therapist to salon magician. Then he toured with his tutor on fairs, national shows, theaters and brothels, until one day bewitched himself: while looking at the jerky movements of pictures in a mahogany cabinet, called Nickelodeon. Tooba became a pioneer in American film production.

Everything becomes a film leaning on cardboard poles or slipping on fine soap

As always in Kristen Wonicki’s bizarre short historical novels, a second original lies as a distorted version of the first in the following plot fold: we experience director Francis Boggs in the middle of his work. This consists mainly of yelling “stop, stop” and “stop recording” as a dark cloud once again blurs the scene, at least for the camera, which is always held as close as possible to the object.

It couldn’t have happened to the clever author, even if she jumped from close-up shot to close-up shot, with funny clumsy cuts. But Boggs also knows how to lend a helping hand to twentieth-century cultural history by moving to California under the eternal sun with a pannier camera and prosthetic beards.

Here as there and on the way to the West, whatever stands, goes and falls, what may wear a hat, toga or cowboy jacket, what leans on cardboard poles or slips on fine soap becomes film. In any case, today’s film composting waste and dreams are more akin to a twisted banana peel than to the upright walk of the Enlightenment. At first, this seems to apply also to the itinerant, chaotic author, intertwined scenes and anecdotes. But far from that. Not only does Kristen Wonicki control her meticulously researched and composed historical material at all times, but she also follows the occasional concrete structure of the first movie, which usually only lasted a few minutes. A movie or two was shot with three or four people a day. Similarly, “Selig & Boggs” will consist of fourteen short films.

More so, I was able to loosely connect the film’s media technology revolution to the philosophical question of the nature of the symbol. “Seligs Polyscope,” Hollywood’s springboard, is not in the Sacred Forest, but in the Edendale neighborhood. Heaven, where things match their names in the Bible, is invoked over and over again. What does the film’s “Redemption of External Reality” (Siegfried Kracauer) bring about the convergence of symbols and objects? One hundred and twenty years later and one media revolution, we are confronted here with one of the most clever and attractive formulations of this anthropological question.

Kristen Wonicki: Selig and Boggs. Hollywood invention. a novel. Berenberg, Berlin 2013/2021. 128 pages, 14 euros.

Animals play an important role. I love them all with blessing. He goes out to the balcony with a chimpanzee to smoke with him. He has five elephants, two giraffes, seven bears, six elk, four kangaroos, two yaks, forty-nine monkeys, and birds. And Polyscope is located in the middle of paradise, in the zoo that would later become the heart of the Los Angeles Zoo.

Selig lives in the house with frequently kissed leopards and a lion named Jackie, who is gently bruised and wet in the knuckles of his fingers. We all know him. Jackie faintly cried twice in front of the specially prepared camera: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s ring. By that time, Selig was already broken and largely forgotten. He did not think that films could last more than half an hour. The fact that D.W. Griffith celebrated a huge hit right next door with several hours of historical drama “Fanatical” is another story. Wunnicke’s “Selig & Boggs” relates it like prehistoric and prehistoric times to a meaningful history.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

Heartstopper Season 3 adds Jonathan Bailey and Hayley Atwell

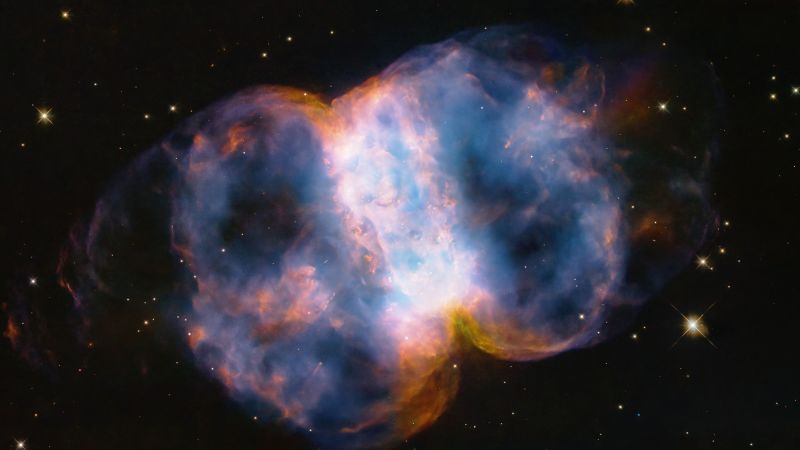

Hubble image may contain evidence of stellar cannibalism in a dumbbell-shaped nebula

Nick Carter and Aaron Carter will be investigated in identity docuseries 'Fallen Idols'