Like any respected philosopher, Marcus Steinweg is a scholar. However, the scholar who directs his work is less melancholy than most of his colleagues to whom he dedicates his thinking. Ludwig Wittgenstein is always at the top of Steinweg’s reading list, but so is Samuel Beckett, and almost a personal preference: Franz Kafka. Steinweg admires his audacity to take strange things seriously as a source of true knowledge. With Kafka There Is No Suffering is the impressive title of one of the many short chapters that make up Steinweg’s latest book, Quantum Philosophy. Once or twice a year, the Professor of Art and Theory at the Karlsruhe Academy of Art presents such narrow volumes of illuminating meta-reading.

Kafka is about “using the means of language to touch the impossible”, to destroy the compassion of the narcissist, to which we might similarly add, Wittgenstein still working his way through. He has great variants of his Tractatus Logicus base sentence ready for that. Wittgenstein expects, writes Steinweg, that music and poetry, as well as art in general, stop at the ineffable—rather than emulate depth. For him, only works of art that keep a distance from the unspeakable, rather than greedily excavate it, were counted. So, what did he feel in antiquity as a sense of decency, characteristic of civilization? Then it would be untenable in relation to contemporary art. So Steinweg continues Wittgenstein’s immortal reason: “If you don’t try to utter the ineffable, nothing is lost. Instead, the ineffable—the ineffable—is contained in what is said!”

Maybe he wants to be a bit enchanted, maybe he’s looking for purity

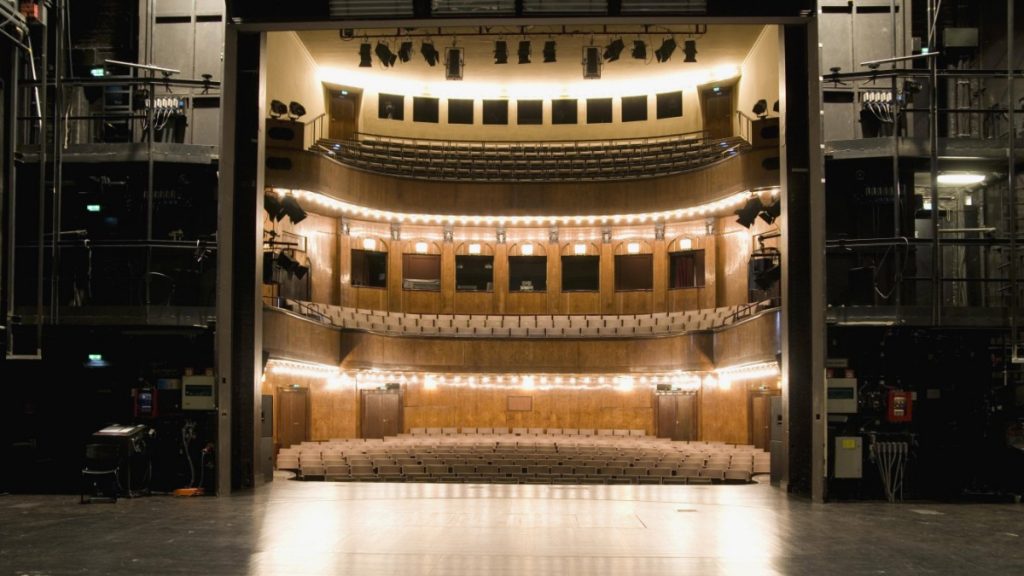

In any case, Steinweg makes no apparent effort to explain to colleagues and to simplify unnecessarily complicated matters. However, his observation of reading encourages confident understanding and creative observation. What helps here is the situation, which can be called sharing distance, an approach that is never ending, yet optimistic. For example, just thinking about the thought process. “Rearranging the scene a little, says Foucault, should be the minimum requirement for any thought which opens to his play, his posture and his theatrical appearance” are the brief instructions. Steinweg’s fondness for theater is unmistakable, he loves miniature productions: “Imagine a sleeping woman with trembling temples. Her head is pressed against your arm. The features are relaxed. Breathing is not audible. She dreams, she convinces you that Nancy is right in saying that the soul never sleeps.”

Marcus Steinweg: Quantum Philosophy. Matisse and Seitz, Berlin 2021. 223 pages, €16.

Jean-Luc Nancy, of Derrida and Heidegger, is also a favorite of Steinweg, who celebrates the act of balancing phenomenology and deconstruction, just as Jacques Lacan brought philosophy and psychology back together after his predecessors painstakingly separated them. Steinweg is magically drawn to these countermoves. Maybe he just wants to be a little intrigued, maybe he’s also looking for purity, “a way out of the core area”, the best performances of “music as a model of seduction”. Steinweg sees Wittgenstein and Kierkegaard agree on this. And Nietzsche, who, according to an anecdote reminiscent of John Cage, went to the piano in a brothel and struck one note—purity or the end of dialectics? Steinweg is attracted to Kierkegaard. The only appropriate form of being a thinker/lover is his passion for openness.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

NYT Wordle answer dated April 23, 2024

Voyager 1 sends data back after NASA remotely repairs 46-year-old probe | space

Inside Cigna – Rainer Flickl / Sebastian Reinhardt – Book Review