The first scene takes place in the classroom and is too gruesome to be reproduced here. In Mrs. Hogel’s art class, students are supposed to draw themselves, including Kirsten, the only talent in the room. On her patrol, Mrs. Hoegel stops at Kirsten’s house, leans over her shoulder and says something, he once said, which could not have been taken as it should be, namely, flattery. Teacher Mrs. Hoegel looks at her student Kirsten’s self-portrait and judges, full of appreciation: “Very successful, respect: the courage to be ugly!”

Kirsten places her hands in front of her face, and only then can the echo of her shoes be heard on the school’s stone staircase. Author Eckhart Nickel remains in the room and continues to paint the first portrait of his art novel Spitzweg. It should be a preliminary sketch of the main characters and really indicate the rules of the game, according to which things will go very smoothly in the following.

Kirsten’s neighbor on the bench is called Karl, and he secured the image discussed by the quick-witted Mrs. Hoegel as the master thief. Eckhart Nickel describes this as the first art heist in Spitzweg and this heist is also successful because it is still not entirely clear at first what intention Carl secured for the crime corpse: to protect his classmate? Or Kamprum for more willful torment from now on?

When parents suffer roof damage, one can feel sorry for their children. But here comes the rescue

The anonymous narrator comes as a third party to what is no longer a covenant. As the only one from the class, watching Carl do this, it’s the beginning of an involuntary complicity between the narrator and the character. It is also another great blow to the author, who applies to his second novel a sentence from Carl Spitzweg, which Nickel himself puts in his book: “Every line with reason, everything thought out, uninteresting.”

Art and the synthetic on all levels, from events to language to acting, even in supporting roles, naturally depart from the possibilities of the story. Although Kirsten, Karl, and the narrator are about to graduate from high school, “Spitzweg” isn’t an upcoming novel in the sense of wild hearts and skinny night dives in a lake. And although the book appears to have been set in an extended present, there is no definitive reference to it. “Spitzweg” is a fantasy in which smartphones do not light up, and electronic cars do not turn. However, “Spitzweg” works well, respect: courage to be artificial!

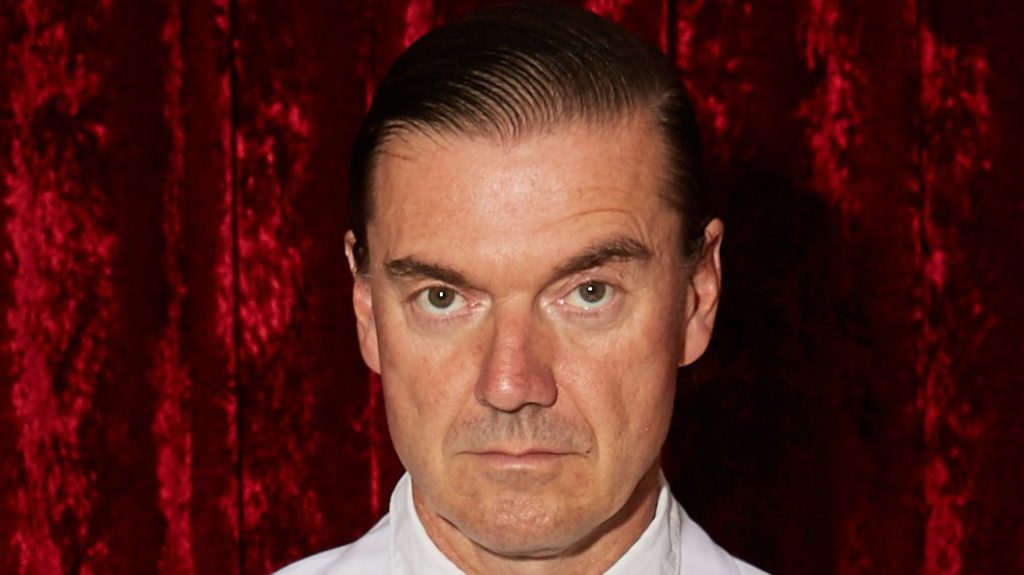

Eckhart Heckel: Spitzweg. Piper, Munich 2022. 256 pages, €22.

(Photo: Eckhart Nickel)

why him? It is first and foremost because of building people and work. Poor Mrs. Heigl’s initial mistake puts the mission of revenge in motion and brings our three heroes together. They develop interesting gradations towards each other. The narrator is in love with Kirsten because she is talented and because she looks like a great head coach on one of the band’s album covers. Vampire Weekendwhich Musikversteher Nickel calls “Vampire Weekend” and thus remains the most obvious code for the real present.

In turn, the narrator says of Carl that he “really was someone whose time was out of date in the best sense of the word”, on which their affinity rested in so far as Carl “I was sure to disdain this presence as much as I did”. Finally, Kirsten is happy with every connection, because her parents’ house doesn’t have one, neither electricity nor heating, that’s it Out of network coverage Because of the alien mother’s sensitivity to everything artificial.

If parents sustain such a very basic roof damage, children can usually only feel sorry for them. However, Kirsten is rescued by Carl and the narrator in a scene that captures so much that makes this book by travel journalist and former pop writer Eckhart Nickel so special.

At the observation point, Chopin’s log becomes a throwing drum

The narrator has withdrawn with Carl into his “art lair,” a secret room somewhere halfway up the stairs of his at least middle-class house. This hiding place is slightly reminiscent of the room of the poor Spitzweg poet, but is also the stage for Karl’s life principle, to celebrate his stubbornness and his artistry without any polite restraint in a semi-classical manner in everything aggressive, from the selection of his good fortune to the spontaneous lecture on the key to a flat specialty in general and specifically in “slow music”“ By Chopin, perhaps the most beautiful music ever written.

The narrator is certainly an art lover, but he is at least less oblivious to the world than Carl. When fugitive Kirsten discovers from the vantage point of Art’s hiding place, which is being threatened by a mob, the narrator grabs the record player and throws Chopin as a discus at the mob. In this sense too, art now has a life-changing influence, and art rarely has a direct impact.

This is ultimately what is “Spitzweg” in a higher sense. After Eckart Nickel already begins his late appearance of “hysteria” with a programmatically suggestive sentence (“Something was wrong with the berries.”), Spitzweg begins with the narrator’s statement: “I didn’t care much about art.” And Spitzweg, then, is a novel about the possibility not to let someone else teach you better, but to educate yourself.

Hugstols Spitzweg in another form, with a dog at least, but still marginally related to the odd natural numbers in temporary proximity when walking.

(Photo: Karl Spitzweg)

Anyone, growing up or later, who realized that there is ultimately no way out of the loneliness that underlies all human beings would be foolish to dispense with art as a life support, antidote and also a dialogue partner. On the cover of Spitzweg, it is not by chance of course that his Hujstols is seen, which is just a word in re-introduction as an event, just as Nickel is teeming with the word “fidelity” and “trouble” and mildew.

In any case, Hughstolz describes a late celibate, with unnecessary distinction, sometimes described as queer by those who see life above all as a task to fulfill all the standards of society rather than individually checked for suitability. In this sense, Karl appears to be the early Hagestolz, so to speak in making To be, while with Kirsten, as the narrator, it seems to be somewhat clear whether Biedermeier can still strike in a very ordinary way, i.e. in the sense of ordinary.

To what extent art can be a useful mirror in the search for the ego and the wonders it holds for each one of us can be read in Spitzweg as well as on the insignificant dangers of fading into social dimensions if one thinks, like Karl, finding a home for art and the synthetic, one cannot That it last any personal relationship.

Eckhart Nickel has managed to write a wonderful book on all of these questions. Thinking frankly about his caregivers is a risk to look out for.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

Nick Carter and Aaron Carter will be investigated in identity docuseries 'Fallen Idols'

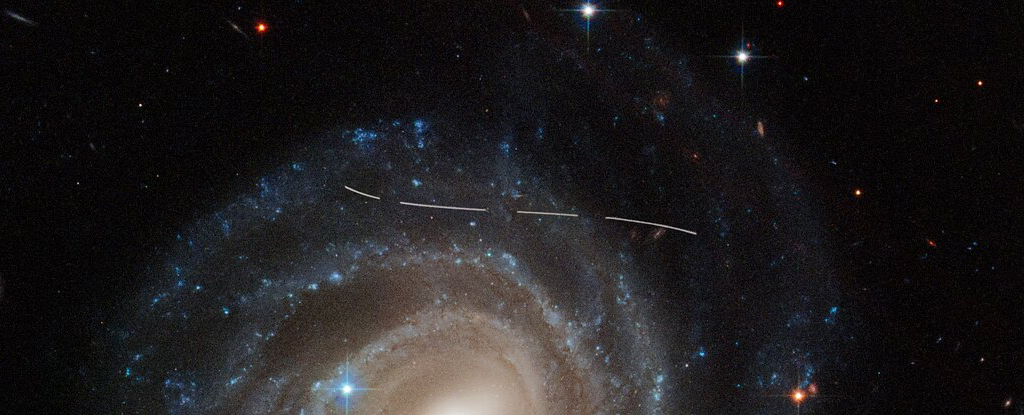

More than 1,000 new additions to our solar system have been hiding in the Hubble archives

The Florence Board Game: Review, Criticism and Testing