La mamma: Even the word has something amazing with its double “m”, and with “a” you can open your mouth gently. And who doesn’t immediately see Sophia Loren moving a bowl of spaghetti with a baby in her arms and another at the tip of her skirt? Or “Mama Roma” by Pierre Paolo Pasolini on Vespa with her son, for whom she is almost tearing herself up? Mothers are an inexhaustible topic in the history of Italian culture. The ubiquitous image of the Virgin Mary seems to promote a deep coexistence between mothers and sons.

In the post-war period, the writer Corrado Alvaro spoke of the increase in “mammismo” – Italy was full of young people whose producers treated them like princes. Romanian psychoanalyst Ernest Bernard, physician Federico Fellini and many other writers coined the term “The Great Mother of the Mediterranean” at the end of the 1960s: because of a deep instinct that excessively corrupted her children and thus increased their need. The result is an ever greater dependency.

Suddenly they know what they have in common: worrying about a child

And surprisingly, there have always been stories in Italy of runaway mothers, and of women who refused to play this role specifically. In 1906, the dazzling Sibylla Alliramo achieved scandalous success by accusing her of her autobiography “Ona Donna,” which is the first manifesto of feminist literature: the author, a well-known journalist, described how she achieved her freedom only at the price of her abandoned son. A few decades later, Elsa Morant, who grew up in a very confusing family situation and had no children, transformed her view: in “Aracoeli” (1982), her hero Manuel describes how his mother rejected him when he was out of childhood. He did not recover from this rejection.

So there is a literary throwback room that reverberates in modern novels on the subject. As with Morante, the children in question take the word: writer Roberto Camori, born in Emilia-Romagna in 1982, is about an agonizing absence in “his mother’s name”. The narrow and oppressive novel begins with the birth that the narrator envisions as a moment of rapprochement between Father Ituri and his wife. Suddenly they know what they have in common: worrying about a child. But after a short time, it turns out that this is exactly what the young mother cannot do: Take a little Pietro in her arms, balance it, and be there for him day and night. Ituri takes on these tasks, and when the doctor recommends staying in the mountains, he goes there alone with the child. When they returned, his wife disappeared.

Roberto Camori, his mother’s name. a novel. Translated from Italian by Maja Pfloj. Kunstmann, Munich 2021,208 pages, 20 €.

Calmly tense, the composing voice adores his childhood in precisely defined images and describes the state of father and son. Mommy is an empty space, taboo, her name has never been mentioned. Like an underground magnetic field, it nonetheless directs all emotional forces. what happened to her? Neither is the abandoned husband raising Pietro talking about it nor the grandparents who have to deal with the loss of their daughter. The moments flash when the extent of the misery becomes clear. On a hike in the mountains, Ituri frightens a family of bears and watches cheerfully as father and mother defend their young. A similar symbol is the scene of Ettore and Pietro bringing a puppy from a farmer who must separate from his mother. His howling lay in their ears for hours. When the dog dies after so many years, Pietro asks his father if the animal has overcome the trauma of separation. Camurri conveys the precarious state of his characters without emotional.

“His mother’s name” appears to have been painted in pastel colors, which is a cautious and principled narrative that leaves much harsh. Sicilian writer Roberto Alajmo made a completely different stylistically self-questioning in 2018 in ‘L’estate del ’78,’ The Summer ’78. This book is not available in German, although it fits perfectly into the popular automatic fiction genre. The beginning is particularly brief: when the Ajamou studies with his friends to high school and then wants to eat ice cream, he finds his mother, long separated from the family, sitting on the sidewalk in her best dress in front of the house. The combination of embarrassment, guilt, and anger at unconventional behavior leaves her with only a few words. He does not yet know that it will be their last meeting.

With the help of pictures, letters, and diaries, the author later conducts research that deals not only with the fascination of the young Sicilian couple in the late 1950s, but also traces the limitations their mother was subjected to. Elena Alamo, an elementary school teacher, was forced to live in an apartment with her uncle, aunt, and later father-in-law. There is a photo of her slouching on her bed, which is clearly her only refuge. So it seemed natural for the little son to find her there most of the time.

Roberto El-Ajmo, Summer ’78. Celerio, Palermo 2018. 174 Seiten, € 15.

Al-Ajamo does not advance a chronological order in his diaries, but approaches the mother in new approaches. The moment on the sidewalk, bathed in sparkling summer light, is repeated many times, as if you were looking at his past through a telescope and refocusing each time until the lines became sharp. This memorial photo was included in descriptions of Christmas rituals, TV evenings, a trip to Paris, and confirmed father-and-father funerals. Ajamou does not care about lineages. Instead, he tries to reconstruct his mother’s medical history, including her medical history. When you read it, it gradually takes your breath away: only in the middle of the book does it appear that Elena was addicted to drugs and spent more time psychiatry than at home. Spasmo Oberon, codeine-containing barbiturates for menstrual cramps, was freely available and in circulation until 1986. In Elena, this led to personality disorders so severe that the family disintegrated.

A year before Alago’s mother’s protocol, Donatella di Petrantonio’s novel “Arminotta” was met with a big response in Italy. Here, the first-person narrator, who came to distant relatives as a baby and returned to her family of origin unknown to her at the age of thirteen, has to overcome a double loss: the social loss of the mother who grew up with her and that biological mother who abandoned her. Michela Morgia had already told in “Acapadora” (2010) about the Sardinian tradition of caring for childless women with daughters from foreign families, and it is noticeable the number of Italian novels in recent years, from Elena Ferrante to Wanda Marasco, about mothers, who manipulate their children Or they reject them. Despite all forms of modern parenting, the mother-child bond has an ancient idiosyncrasy with many shades.

Donatella de Petrantonio, Armenia. a novel. Translated from Italian by Maja Pfloj. Publisher Antje Kunstmann. Munich 2018, 222 pages, 20 €.

The extent of the painful experiences of this kind of mothers themselves is evidenced by the intertwining in the biographies of two women who were in a public place and who were neither permitted nor wishing to keep their children: one of them was the famous reformatory teacher and feminist activist Maria Montessori, who worked for himself in 1896 advocating for the payment of wages of women and men And he developed pioneering methods of raising children. Unnoticed by everyone, she gave birth to a son, put him with a foster family, and her “nephew” only took him when she was fourteen years old. Who really is found in her will. There was clearly no place for a child, and an illegitimate one at that, in a female’s career.

This was the case in 1957. At that time, nineteen-year-old Claudia Cardinale was offered her first major movie roles. She got pregnant through rape and decided to keep the baby. But at the request of her producer and lover Franco Cristaldi, with whom she worked permanently, she had to secretly give birth to her son in London, bring him to her parents and forbid him to be a younger brother. Longing remained an insatiable hunger for all.

Perhaps precisely because motherhood was culturally charged, it has come to extreme manifestations: pampering with euphoria to retirement age or severing relationships. Divorce only became possible from 1970 onwards. And until 1975, Fascist Family Law No. 151 was in effect in Italy: the wife was not allowed to freely choose her place of residence, and she was not allowed to decide how to raise her children. Its abolition was due to the women’s movement. The women had read Sibilla Aleramo.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

Heartstopper Season 3 adds Jonathan Bailey and Hayley Atwell

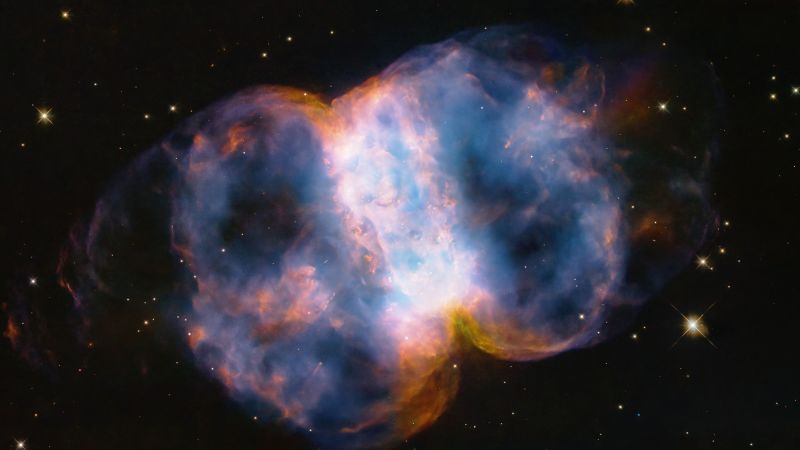

Hubble image may contain evidence of stellar cannibalism in a dumbbell-shaped nebula

Nick Carter and Aaron Carter will be investigated in identity docuseries 'Fallen Idols'