The current pandemic has caused many people to spend more time with themselves than usual, perhaps wondering who they were already dealing with. “Alone: In Bad Company,” defines The Devil’s Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce. It seems like a good time for writers like Rudiger Safransky’s Being Alone – A Philosophical Challenge.

Of course the author does not treat the topic as a philosophical challenge, but rather as is his way Rather, in the form of a personal picture. In 16 chapters and several interludes, the following appear alongside others: Martin Luther, Montaigne, Rousseau, Diderot, Kierkegaard, Stefan Georg, Sartre, Jaspers, Hannah Arendt, Ernst Ginger, and the only real surprise Ricarda Hoch.

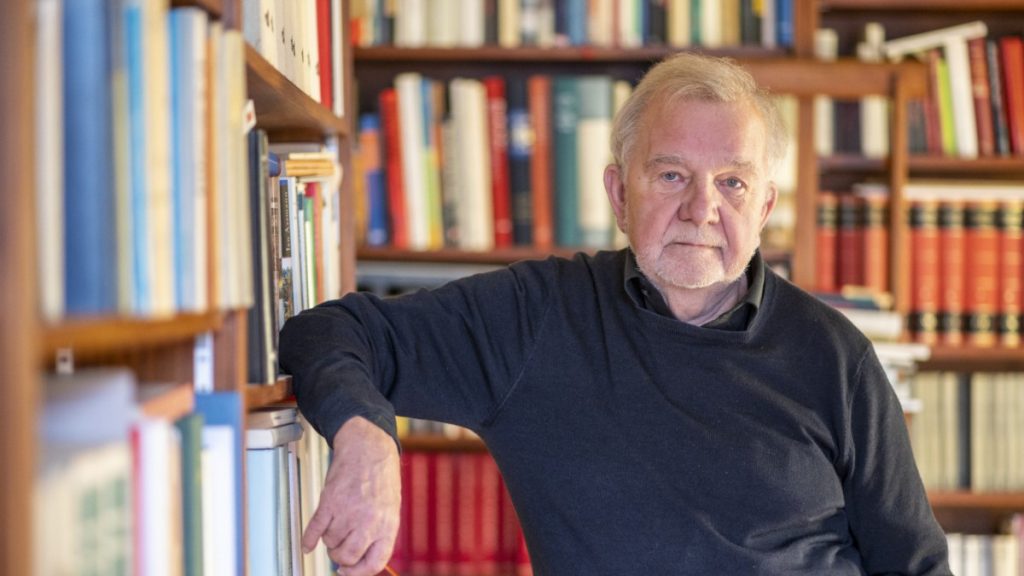

Rudiger Safransky: Being alone. A philosophical challenge. Hanser, Munich 2021. 285 pages, €26.

Accordingly, the individual thing about them is quite impressive. For most people, the investigation is limited to how they interact with their environment as individuals, which by nature is always. As an individual, Martin Luther may have been so surprised by that storm in the open field that forced him to vow that he must become a monk – or else he is His biography, small and large Shaped by life as a whole and for everyone. For Diderot and his work ‘Rameau’s Nephew’ as well as for Stendhal, the fact that their ambitious and adaptable existence is explained almost entirely by their social performance must be especially true. They even become so fully immersed in their social roles that one has to appreciate this as an individual achievement: the dialectical line does not really catch on.

It’s never too late to be single

Then the individual appears as a philosophical problem only in the narrow sense with Kierkegaard, Max Stirner and the existentialists of the twentieth century. If one does not know the relevant thinkers at all, one may benefit from Safranski’s loose presentation and paraphrase, including rich anecdotal material; Otherwise rather not. Safransky does not have to present a static concept, or strong thesis, in which the more or less random series, the individual cases, are supported and brought together to form a recognizable unit. The best are the many quotes with which he distinguishes his heroes. However, a book to be adopted as such cannot really be a good one.

In conclusion, he chooses like Kafka “before the law” and follows a seemingly irresistible impulse to explain it: “But at least as long as you are alive, it is never too late to enter, for being an individual.” Among the many interpretations that this story about the countryman and the janitor has already found, this story stands out for its unusually sunny character.

“Explorer. Communicator. Music geek. Web buff. Social media nerd. Food fanatic.”

More Stories

A fossilized creature may explain a puzzling drawing on a rock wall.

MrBeast Sued Over ‘Unsafe Environment’ on Upcoming Amazon Reality Show | US TV

Watch comets Lemmon and SWAN approach Earth today